WISCONSIN’S WARNER

I have encouraged you to find monuments, plaques, statues and other tributes to aviation history in your home town or during your travels. For those of you who are curious, there is no need to leave home. The Internet can take you anywhere in the world to find both the famous and obscure commemorative benchmarks you seek for a famous aviator, aircraft designer, flying field or maintenance shed. Or, as it recently happened for me, you might be led to a chapter in aviation history quite by chance.

Years ago I assisted in the donation of memorabilia to various museums from the family of pioneer aviator, A. Roy Knanbenshue. I kept an intriguing copy of a photograph that pictured Knabenshue and his wife, Mabel, with Wright Exhibition Team aviators Walter Brookins and Frank Coffyn. Scribbles on the reverse of this picture also identified Mrs. Frank Coffyn, Mrs. Walter Brookins and A.P. Warner, as well as an unidentified woman wearing a Native American “whirling stick” belt buckle. I wondered why I didn’t know who A.P. Warner was or how he knew Knabenshue.

A quick Internet search revealed that Warner had flown a Curtiss biplane. Since the Wrights and Curtiss were competitors, if not adversaries, I wondered why I didn’t know more about Warner and how he met Knabenshue.

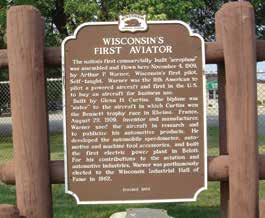

I soon found a bronze plaque on a monument in Beloit, WI, where Warner flew in 1909.

The memorial to Warner was placed there during the 1960s when the organization known as the Early Birds of Aviation recognized that Warner had “purchased, assembled and taught himself to fly a Curtiss Pusher.” A nearby state historic marker gave further details which became the key to a chapter in American aviation previously unknown to me.

D.O.M.’s offices are in Wisconsin, so it was serendipitous for me to identify Warner as the first person to fly an aeroplane in that state at a spot less than 25 miles from my editor’s office.

Making Things

Arthur Pratt Warner [1870-1957] was born in Florida, but his family soon moved near Beloit, where his father opened a business as a pattern maker. This trade required the combined skills of engineering and metalurgy for making molds and castings. As children, Warner and his brother Charles learned how things were made and envisioned themselves as future inventors. Late in life, Warner wrote an autobiographical sketch titled, “Making Things,” which revealed a man who was both a life-long tinkerer and devoted to his family. Young Warner briefly lived on a family farm where he disassembled and rebuilt equipment and machinery just to see how it worked. His first invention was a battery-powered motor for his grandmother’s sewing machine. Although he was bright and mechanically gifted, Warner did not aspire to be a scholar, and instead he chose to be self-taught. He later recalled that he learned a great deal of practical science from “Electric Engineering” magazine and later from a two-year international correspondence course in electrical engineering. This independent learning style stuck with Warner throughout his entire life, and he was openly disdainful of high-paid degreed engineers who had not actually built anything.

By age 21, Warner was working for an electrical power company in Beloit, improving equipment designs until he became a partner in the business. When that venture left him in debt, he was hired as an engineer by A.O. Fox, owner of the Northern Electric Company (NEC). Fox grew to depend upon Warner’s inherent skills to improve production and the two men became long-term friends. Warner worked for NEC several years until he was promoted to sales manager, requiring a move to Milwaukee, WI. While working for NEC, Warner continued to tinker and file patents on various inventions. By 1900, Warner was married and had his first son. NEC changed hands until it became part of the General Electric Company (GE), based in New York City. It was in New York where Warner met the famous mathematician Charles Steinmetz [1865-1923], whom he greatly admired.

Working for GE was both gratifying and lucrative, and by 1904, Warner’s job required a brief move to Chicago, where his second son was born. Somehow, he and his brother Charles had found time to invent what would eventually be adapted as a speedometer for automobiles. Warner, now 34, wanted to return to Wisconsin and be his own boss. The brothers formed Warner Instrument Company in Beloit, and it expanded to produce more of Warner’s many inventions to improve automobile safety.

Joining the Air Minded

On a sales trip to New York City, Warner was introduced to Augustus Herring [1867-1926], who was then affiliated with aviator and aircraft designer Glenn Curtiss [1878-1930]. Warner’s memoires revealed that, as a child, he had designed many kites and had always been fascinated with flight. When Herring asked Warner to help him develop an aircraft engine (promised to Curtiss), he jumped at the opportunity. He later wrote that although the engine was powerful for its weight, it continually failed due to overheating. His relationship with Herring was short lived but he had made his first contact with the movers and shakers in aviation at the time. By 1906, Warner had joined the fledgling Aeronautical Society of New York, mingling with men and women with a passion for flight and new inventions. Among these new associates were the marketing team of Wyckoff, Church and Partridge, which sold automobiles. By 1909 it also represented Herring-Curtiss Aeroplanes. Curtiss was selling replicas of the plane in which he won the famous Gordon Bennett Race for America at the Rheims Air Meet in France just months before. No one in America had yet manufactured an aeroplane solely to sell to the general public. This was a benchmark in American aviation history not lost on Warner.

Theorizing that aviators were newsworthy, Warner expected free advertising for his business by becoming the first individual in the U.S. to purchase an aeroplane. Warner left a check with Wyckoff, Church and Partridge for $6,000 and returned to Beloit. His Curtiss Pusher arrived as a crate of parts without assembly instructions. In typical fashion, Warner built the aircraft without a manual and taught himself to fly.

Wisconsin’s Big Cheese and the Aha!

On Nov. 4, 1909, at a height of 50 feet, Warner soloed for a quarter of a mile. The flight guaranteed Warner’s legacy as the first person to fly an aeroplane in Wisconsin and placed him among the earliest aviators in the world.

Warner took his Curtiss Pusher to the 1910 Dominguez Air Meet at Los Angeles, but there is no record of a flight. His memoires disclose that he worked as a “timer” among the officials, including meet organizer A. Roy Knabenshue.

Aha!

Warner was now shoulder to shoulder with the most famous aviators in the world, but his own public flying was minimal. He never competed in exhibition flying. Within the year, Warner sold his Curtiss to another flier.

The Warner brothers sold their company in 1912, making them millionaires. Five years later, Warner started another company in Chicago, producing automobile and truck parts. He is well recognized as the inventor of an electric braking system and a power clutch. Warner retired at the age of 64 and lived the rest of his life in Beloit.

Finding the historic markers for A.P. Warner at Beloit is a fitting end to this past year’s quest for our “aviation ancestry.” I now know how Warner and Knabenshue met, but not precisely where, or when they posed for their group picture. It remains to be discovered.

Next year’s articles will include America’s oddest early aircraft that didn’t fly.

Happy New Year 2015!

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author who has received the DAR History Medal and honorable mention from the New York Book Festival. She has appeared on the History Channel and in PBS documentaries. For more information, visit www.GiaBKoontz.com.