Two Days in April One Hundred Years Ago

The time is coming when we shall find the means of transportation by bird-like flights as safe and satisfactory as transportation by steamship or locomotive and with still greater speed. This is not to be accomplished by racing or doing circus tricks in the air at aviation meets. - Harriet Quimby, Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, 1911

In the summer of 1910, New York photojournalist Harriet Quimby joined an Aero Club that made model airplanes. Some of its members were to become notable aircraft inventors and aviators, including A. Leo Stevens and Lilian Todd. The following year, Quimby became America’s first licensed female pilot and exhibition flier. Other aviators chose bi-planes built by Curtiss and Wright, but Quimby once quipped that she felt it prudent to follow nature’s design of birds, which had one set of wings. Her training and exhibition flights were in Bleriot-type monoplanes, copied from the French factory-built aircraft designed by Louis Bleriot. It is no wonder Quimby and other aviators loved the Bleriot with its graceful, bird-like frame, easily identified by air meet spectators. As the sun shone through its diaphanous wings, some called it “The Dragonfly.”

If you ask a grammar school child to draw an airplane today, chances are it will probably resemble the outline of a 1911 Bleriot, with a high wing attached to a sleek tubular fuselage and an upright tail. Essentially, an airplane began looking like an airplane (or, at least a 1940s tail-dragging Cessna,) when Antoinette, Deperdussin, and other monoplanes showed up on airfields. The most popular monoplane of that era was the Bleriot series, built in France until about 1914, with licensed copies manufactured in several countries. Beginning with the Bleriot I, designer Bleriot and Gabriel Voisin tested biplanes on land and water without great success.

Disassociating himself from Voisin, Bleriot (with Raymond Saulnier) continued designing aircraft, and by 1908, the Bleriot XI (nicknamed the “Onze,” which means “eleven”) included a three-wheel undercarriage, front wheels mounted on a shock-absorbing frame, pylon support for wings, a tail assembly of a small rudder and pivoting elevator, and wing-warping controls (copied from the Wrights).

In 1909, at the controls of his “Onze,” Bleriot became the first person to fly across the English Channel, which made him and his monoplane famous. Soon his flying school and aircraft factory were busy producing several versions of the Bleriot, modifying the design for military and sport use.

Tragedy and Triumph

In the spring of 1912, Quimby arrived in England with a goal to become the first woman to solo across the English Channel. Her plan was to borrow a Bleriot from the famous French flier and make his 1909 flight in reverse, taking off from the cliffs of Dover at the narrowest distance over the channel to Calais, France.

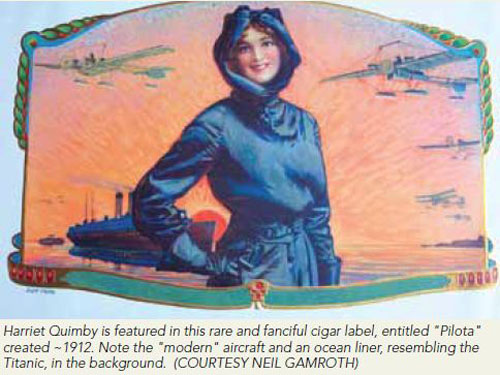

Meanwhile, the European press was preoccupied with the debut of the Star Line’s luxury liner, RMS Titanic. On April 1, 1912, the Titanic passed its sea trials and headed for Southampton, England, to pick up passengers. That same day, the skies over the English Channel cleared just long enough for England’s famous aviator, Gustav Hamel, to fly Eleanor Trehawke-Davies from England to France, making her the first woman to cross the channel by air. Although a passenger and not at the controls, Trehawke-Davies stole much of Quimby’s thunder. As she waited in the south of England, Quimby did not let the foul weather nor this news impede her resolve.

Two weeks later, with predictions for a few days of clear weather, Quimby was eager to make her flight. Although experienced in monoplane types, she had never flown a factory-built Bleriot, and missed her chances to make test flights prior to her cross-channel attempt. On the morning of April 15, Quimby and the rest of the world was shocked to read that more than 1,500 people had lost their lives when the Titanic sank after striking an iceberg. As a New Yorker, Quimby probably knew some of the victims personally, if not by association as a reporter.

Nevertheless, the following day, April 16, she went forward with her own entry into the history books. Her flight was perilous, and others had died making the effort. Without a parachute, safety belt or life vest, Quimby’s only precaution was a pontoon that Bleriot affixed to the fuselage in case of a water landing. From the cliffs of Dover, Quimby flew more than 25 miles in about one hour, making a beach landing near Equihen, France. Her flight had been perilous, in extreme cold and over treacherous waters. Exulting in her personal triumph, Quimby returned to the U.S. several weeks later. Headlines continued to be dominated by the Titanic disaster, and her achievement was not celebrated with major recognition at the time.

Eager to participate in the Harvard-Boston Air Meet, Quimby was soon back on Long Island and making test flights in her newly purchased two-seat, 70hp Bleriot. It was to be her last public appearance.

On July 1, 1912, Quimby and her passenger were both thrust out of their seats and fell to their deaths as she flew an exhibition flight around the Boston Light in Massachusetts. A design flaw in the tail assembly was later determined to be cause of the sudden mid-air imbalance which Quimby could not control. This had not been the first accident of its type, and Bleriot thereafter improved the elevator design.

There’s a Plane in the Barn

Although several Bleriot copies now reside in museums, an original built at the Bleriot factory in France is rare. The National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, D.C., displays a restored Bleriot which continues to inspire collectors to search for the mythical “airplane in the barn.”

Swiss-born, John Domenjoz, became such a proficient student at the Bleriot school in Pau that he was hired as an instructor. He bought a Bleriot XI and made exhibition flights in Europe, demonstrating loops, and other daring stunts earning the nickname, “Upside-down Domenjoz.” He took his Bleriot to New York in 1915, thrilling spectators with spirals and spins near the Statue of Liberty. Crossing the Atlantic became routine for Domenjoz for the next four years as he alternately made exhibition flights in Virginia, Washington, D.C., Tennessee, and Cuba, and returned to flight-test SPADS in France. Back in the U.S., Domenjoz stored his “Onze” in a barn and moved to France during 1919, where he lived for the next 17 years. He returned to the U.S. in 1937, thrilled to locate his beloved Bleriot which, for back storage rent, had been sold to a New York museum. In 1950, the NASM bought the Domenjoz Bleriot, and it sat for another 28 years untouched. Between 1978 and 1979, it was restored and remains on display in the NASM’s “Early Flight” exhibit.

This April will mark the centenary of the aviation triumph of Harriet Quimby’s cross-channel flight in a classic monoplane — the Bleriot XI. It will also be the 100th anniversary of the Titanic tragedy.

What happened to Quimby’s cross channel Bleriot and her two-seat Bleriot? The borrowed Bleriot XI returned to its hangar in France. The (military modified type) two-seater used in Quimby’s fatal flight landed upside down in the shallow waters of Dorchester Bay near Squantum, Mass., and was sold for parts by her manager through advertisements in various aviation magazines. The Titanic broke apart and remains on the ocean floor — but the popular film by the same title has re-surfaced in 3D.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.