Take a Train — Part I of III

By Giacinta Bradley Koontz

On June 20, 1929, Charles Lindbergh and his hand-picked team of pilots flew across the U.S. on the first test flights for a newly-formed commercial airline that was the beginning of modern air travel as we now know it.

Small airlines like Varney and Western Air Express filled the Americas’ appetite for air travel in the late 1920s. Many like Varney vanished, but by 1929, Western was America’s largest passenger airline flying its fleet of aircraft from the Pacific coast to its easternmost destination at Kansas City, Kansas. Western’s air network covered 4,000 miles among cities in Texas, New Mexico, Wyoming, Utah, Colorado and California. Night flying was uncommon and long-distance air travel meant overnight stays. Meanwhile, at temporary headquarters in Washington, D.C., Clement M. Keys organized a dream team of America’s most talented, famous and influential aviators, engineers, railroad executives and businessmen to build a coast-to-coast airline system. They called their new company Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT).

The Big Idea

TAT was more than a new airline. It was a social phenomena. Once partnered with TAT, the Pennsylvania and Santa Fe railroads created specially-appointed sleeper trains with stations at TAT’s airports so that passengers could transfer quickly. TAT also partnered with the popular Fred Harvey restaurants at its terminals which were as architecturally stunning as they were functional. Best of all, TAT had the full endorsement of America’s flying heroes Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh. Earhart was hired as an assistant to the travel manager, while Lindbergh was the chairman of the technical committee. Always “hands on,” Lindbergh supervised every detail pertinent to aircraft equipment and personnel, and was to pilot the inaugural eastbound flight. Even though travel was as much on the rails as in the air, TAT became known as the “Lindbergh Line.” When necessary, travelers were transferred by luxurious Aero Car between an airport and train station. TAT’s transportation system was in perpetual motion. It was a new concept that prompted TAT’s critics to call it “Take a Train.”

TAT was more than a new airline. It was a social phenomena. Once partnered with TAT, the Pennsylvania and Santa Fe railroads created specially-appointed sleeper trains with stations at TAT’s airports so that passengers could transfer quickly. TAT also partnered with the popular Fred Harvey restaurants at its terminals which were as architecturally stunning as they were functional. Best of all, TAT had the full endorsement of America’s flying heroes Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh. Earhart was hired as an assistant to the travel manager, while Lindbergh was the chairman of the technical committee. Always “hands on,” Lindbergh supervised every detail pertinent to aircraft equipment and personnel, and was to pilot the inaugural eastbound flight. Even though travel was as much on the rails as in the air, TAT became known as the “Lindbergh Line.” When necessary, travelers were transferred by luxurious Aero Car between an airport and train station. TAT’s transportation system was in perpetual motion. It was a new concept that prompted TAT’s critics to call it “Take a Train.”

Despite the obvious importance of rail service, nothing was more iconic than TAT’s fleet of aircraft built in Detroit by Henry Ford and his son, Edsel. Fascinated with flight for years, the senior Ford was tempted, but not convinced to design and mass produce aircraft using the same methods as he had already proven successful for automobiles. He met William “Bill” Stout in the mid-1920s and was soon in the aviation game.

The Ford Tri-Motor

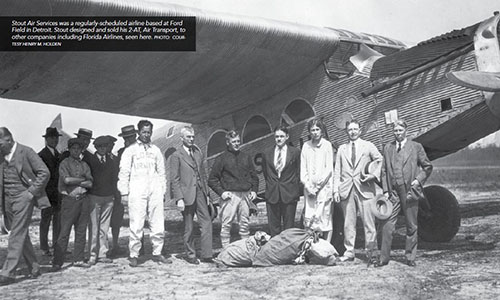

For decades, aircraft were constructed of wood and fabric without much consideration for passenger comfort. Open-cockpit biplanes were operated by one pilot and passengers literally took a back seat to cargo, often sitting on top of mail bags. Experimental designs of all-metal aircraft had already been known without major success in the U.S., but Stout changed all that when he built the 2-AT Air Transport in 1924. Stout, an inventor and entrepreneur, had been developing all types of vehicles when he formed the Stout Metal Airplane Company in 1922 and attracted the attention of Ford.

Sturdy and aerodynamic, Stout’s 2-AT was a monoplane with an all-corrugated metal fuselage. It held five passengers who sat in chair seats, their luggage stowed in separate compartments. In addition to passenger comfort, Stout believed that all commercial aircraft should require two pilots. The enclosed cockpit accommodated a pilot and co-pilot who were protected by a windshield. Stout intended to build a fleet for his own commuter airline service originating in Detroit. The Ford father-and-son team was less interested in running an airline than they were in the prospect of adapting their automobile mass-production techniques for the construction of aircraft.

Partnering with Stout to build larger all-metal aircraft, Ford built a factory, hangar and flying field next to his Detroit automotive plant. Now a division of Ford Motor Company, Stout All-Metal Airplane continued perfecting and developing new passenger-carrying aircraft. Through several design phases, Stout failed to build the next generation of passenger-carrying aircraft to Ford’s satisfaction. With Stout sidelined, Ford’s own engineering staff quickly built an aircraft with one engine on the nose and one on each wing. The tri-motor concept, basic all-metal fabrication, and many other engineering ideas originated with Stout, but the ultimate aircraft design was actually a combination of many talented people. Stout continued his business relationship with Ford in other ways, not the least of which was his marketing skill, driven by his passion for promoting air travel. From Ford Field, Stout’s commuter service kept busy, and when he separated completely from Ford he went on to invent more aircraft, cars, motorcycles, buses, train cars and even portable houses. Meanwhile, Ford rolled out its first Tri-Motor in June 1926.

The Ford Tri-Motor had a wing span over 75 feet and was 50 feet long. It was powered by three nine-cylinder Wright Whirlwind J5 engines. The entire fuselage was made of corrugated duralumin, and the wings were fabricated using internal metal bracing which Ford bragged made his tri-motor stronger than anything built thus far. The Ford Tri-Motor could accommodate 10 passengers and three crew (all male): a pilot, first officer and a courier, “for passenger comfort” in the air and on the ground. These couriers were the first flight attendants and wore seasonal uniforms (white for summer and dark blue for winter). Creature comforts onboard the Tri-Motor included a toilet and folding tables upon which food was served. In the winter, the Tri-Motor was heated. In summer, passengers were advised to cool down by opening their window.

According to historian Henry Holden, Ford met Lindbergh at Ford Field following the Lone Eagle’s trans-Atlantic flight of 1927. In a remarkable moment of aviation history, Lindbergh took the senior Ford for a ride in the Spirit of St. Louis in exchange for a chance to take the controls of a Ford Tri-Motor. Lindbergh was impressed with the aircraft’s performance, and according to Holden, “It was the only time Henry Ford ever flew in one of his Tri-Motors.”

When Lindbergh signed on with Keys to form TAT, it is no wonder that his first choice of aircraft was the latest Ford Tri-Motor, the 5-AT, powered by three Pratt & Whitney 420hp engines.

On July 8, 1929, TAT’s Ford Tri-Motor “City of Los Angeles” made its inaugural eastbound flight from California, with Lindbergh at the controls. At the same time, the “Airway Limited” left New York’s Pennsylvania Station, carrying Amelia Earhart headed to the airport at Columbus, Ohio. There Earhart boarded as a passenger on TAT’s westbound flagship, “The City of Columbus.”

TAT was officially in business. Behind the glamour of luxury air travel, they had invented new technology for air and ground operations, and built airports where there were none. They originated some of the first commercial night flights, scenic air tours, and regular time schedules. Before TAT acquired Maddox Air Lines and then became Trans World Air Transport (TWA) in 1930, they had flown thousands of passengers across the U.S. Convenient modern air travel had arrived, and with it followed unexpected challenges for passenger safety. (To be continued.)

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.