The Plane that Flew on the Ground

The Link Aviation Trainer device is the center of attraction at the Mayfair miniature golf course in Los Angeles. Such devices would make a valuable adjunct to the multitude of miniature golf courses that now dot the country. – Science and Invention, November 1930

As I write this, the search for the missing Malaysian 777 airliner, Flight MH370, continues in the Indian Ocean. Of special interest to me has been the use of underwater drones such as the Bluefin-21, made in Quincy, MA. I was once a draftsman for a company in California that made remote-controlled vehicles (RCVs), now known as remoteoperated vehicles (ROVs). As in aviation, test pilots made dives in the first manned submersibles, and similarly, there were accidents and fatalities. In 1973, a routine dive took the lives of Albert Stover and Clayton Link, the son of the four-man underwater vehicle’s inventor, Edwin A. Link Jr., better known in aviation as the “father of the flight simulation.”

“A Dangerous Thing”

It would be unthinkable today for a student pilot to step into an aircraft and make a solo flight only after a few hours of ground instruction. Yet, prior to WWI, the seating arrangements as well as the amount of weight an aircraft could carry aloft determined that many would-be pilots had to go it alone from the very first minute. This was true in most monoplanes, such as the Bleriot type in which students sat behind the controls in a series of taxiing and low-level hop exercises before their first takeoffs. First-flight solos also occurred in biplanes such as those made by Curtiss and Wright. To make matters more difficult, learning on one aircraft did not necessarily apply to the controls of another. Curtiss aircraft used a yoke, similar to an automobile steering wheel.

“Every movement — pushing and pulling, turning the wheel and leaning — was natural and instinctive,” writes historian Tom Crouch. Not so with the Wright machines. Says Crouch, “A new pilot had to think about flying a Wright machine, and that was a dangerous thing.”

At most ground schools, students learned what was then known about weather, air currents and altitude effects, although the center of gravity was not yet understood. Few instructors could offer more than a makeshift simulator using a barrel balanced on wood planks and hung by ropes from a winch. Inside his factory, Orville Wright took the engine off of an old, unused aircraft and affixed it to sawhorses mounted to the floor.

Young Lt. Henry “Hap” Arnold later described his training during 1911 on what Crouch believes is the world’s first aircraft frame used for a flight simulator: “The lateral controls were connected with small clutches at the wingtips, and grabbed a moving belt running over a pulley. A forward motion, and the clutch would snatch the belt, and down would go the left wing. A backward pull and the reverse would happen. The jolts and teetering were so violent that the student was kept busy just moving the lever back and forth to keep on an even keel. That was primary training, and it lasted for a few days.”

Graduating pilots from the Wright school averaged about ten days of lessons, with three or four hours of flying time, while some schools offered even less instruction. Hundreds of aviators became proficient; many later flying professionally in exhibitions and air meets. Aircraft at the time were constantly redesigned to keep up with aeronautical science. Aviation accidents were common and fatalities imminent. It didn’t take long for pilots and aircraft designers to realize they needed better pre-flight training on the ground. The answer came from an unexpected source.

The Missing Link to Flight Training

“Ed Link was a neat guy,” wrote his friend, Harvey Roehl, after Link’s death in 1981. Roehl was then writing for his colleagues in the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors Association (AMICA). “Ed was always the happiest when he was in work clothes, tinkering with some new device or gadget in his workshop,” wrote Roehl.

Edward Albert Link Jr. [1904-1981] earned his membership with AMICA due to his family business of building and repairing pianos and organs. Link was obviously bright but uninterested in classroom academics. At age 16, he left school to work for his father.

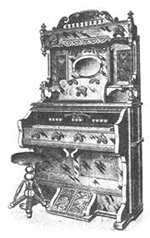

In 1910, when Link was six years old, his family moved from Indiana to Binghamton, NY, where his father kept the music going at the Link Piano Company. At the turn of the 20th century, player pianos and organ recitals were popular family entertainment, keeping the Link Piano Company busy. Young Link mastered the art and the mechanical engineering that combined bellows and gears to produce the variable sounds of musical instruments.

By 1927, the sound of an aircraft engine lured Link away from the sound of the piano. During 1928, he worked as crew for barnstormers, learning to fly by observing and an occasional lesson. He determined quickly that the cost of training in an aircraft was not only expensive but could also be dangerous. Link knew he needed more flying experience without the inherent risk.

“He began to construct a simulated cockpit that could be set up anywhere, yet could move and respond to controls similar to that of an airplane,” wrote Link’s biographers Robert B. Parke and Lloyd L. Kelly. In 1929, Link built the invention that would change flight instruction forever.

“Link applied the principles he had mastered in building fine organs to the design of his new flight training device,” wrote an authority on the history of simulators. “The pilot trainer’s stubby wooden cockpit fuselage was mounted on organ bellows that Link had borrowed from his father’s piano factory. An electric pump drove the organ bellows that allowed the trainer to bank, climb and dive as a pilot operated the controls in the cockpit.”

Link patented his trainer, which he called the “Pilot Maker,” in 1929. Before it caught on as a serious flight-training machine, Link adapted his simulator for use at amusement parks. Children slipped coins into a slot to begin the pitch and yaw movements of the “toy airplane.” Park and Kelly described the importance of the “Pilot Maker” after it was purchased by the US Army Air Corps in 1934:

“Originally used as an instrument trainer for the instruction of Army mail-carrying pilots for all-weather flights, its full potential as a ‘plane that flies on the ground’ became apparent when, with the outbreak of WWII, the Army was faced with the task of teaching thousands of men to fly as quickly as possible. The young Link Aviation Company turned out the ‘blue boxes’ that were used to train more than half a million airmen throughout the world.“

It was the beginning of Link’s successful simulators, which adapted and mimicked jets, jet bombers, helicopters, airborne gunnery and everything that followed in the progression of aerospace. In 1970, with unabashed appreciation, astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr. wrote, “Simulators are helping to develop a safer and more carefully planned program for accomplishing our future goals in air and space.” More than 40 years later, it is difficult to find any aspect of modern piloting that is not linked (pardon the pun) to some type of simulator.

Link continued to perfect his inventions at the head of several companies for decades. He pioneered simulator design in upper space, inner space and eventually, as Shepard predicted, outer space.

Link died at age 77 in Binghamton. Among inventors all over the world, the man who created the “the plane that flew on the ground” is remembered as the father of flight simulation.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author who has received the DAR History Medal and Honorable Mention from the New York Book Festival. She has appeared on the History Channel and in PBS documentaries. For more information, visit www.GiaBKoontz.com.