Part II of II: Lucky 13 Hugh Robinson – Flying for Money

By February 1911, Hugh Robinson could have quit aviation altogether and left a legacy of remarkable contributions to the design of Glenn Curtiss’s hydroaeroplane. Robinson chose instead to remain in the aviation game and became a member of the Curtiss Exhibition Flying Team. Not yet licensed, and with little flying time, Robinson was considered a novice among seasoned and already-famous fliers such as James Ward, Lincoln Beachey, Cromwell Dixon, Charles Hamilton and Bud Mars.

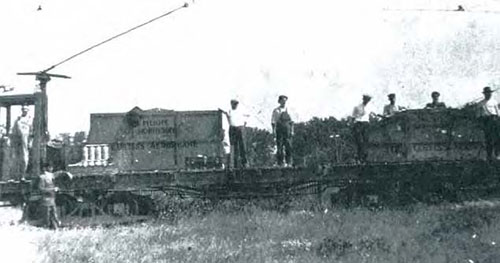

The 1911 Curtiss team of 18 members was separated into small groups of between one and five fliers who traveled by truck and train. Aviators were hired by townships, an aero club or local newspaper for a county fair or fourth-of-July celebration, and occasionally to compete for prize money in races funded by wealthy businessmen. A flier who wrecked aircraft was paid less since the going price for a replacement was between $4,500 and $6,000 (inflated to $104,000-$140,000 in 2013). The risks were high but so was the pay. Flying for money was one of the most lucrative professions in the world during 1911. An aviator was paid based upon his box-office draw which was the reason a flier was compelled to attempt dangerous stunts. Robinson was hired at $25 dollars per week (inflated to narly $600 in 2013) but his pay scale rose with his fame.

Robinson’s mechanic, W.J. Shackleford, and his assistants were among the best and were also well paid. Shackleford oversaw the teardown and transport of aircraft immediately following an air show. With little sleep, Shackleford supervised the reassembly of “Number 13” in a barn, a tent, or an automobile garage offered in substitute for a shed (known now as a hangar).

Robinson’s team traveled north to Canada and south to Georgia and Mexico, west to Oregon and east to New York, but the majority of shows were in the central states.

Another “Lucky 13”

There were weeks when Estia, Robinson’s wife, kept their two boys home in Neosho, MO, while he was far away. Days of anxiety passed between reassuring phone calls that he had not been injured nor killed. The family also joined the flying circus team for several weeks as they traveled by train. Estia home schooled their children en route, and no doubt met and bonded with the families of other aviators. Also traveling with her husband between May and September 1911 was Adelaide Ovington, the recent bride of aviator Earle L. Ovington (1879-1936).

In 1920, Adelaide published her memoirs, “The Aviator’s Wife,” which is her personal, if not romantic, account of “life among the fliers.” Like Robinson, Ovington had several significant reasons to affix the “lucky” number 13 on the tail of his aircraft, which was a Bleriot-type monoplane. Ovington received his license to fly at Pau, France, and later hired two French mechanics to tune his Gnome engine while on tour. “A good mechanic,” Adelaide wrote, “is half the battle.”

Ovington flew independent of a team and Adelaide was by his side every moment on the ground. Adelaide packed and unpacked their suitcases, watched the crew work through the night in preparation for the morning’s show, and was there to kiss her husband good luck before each flight. Newspaper reporters, photographers and fans left the newlyweds with little privacy. On the road, Adelaide collected programs and newspaper clippings for a scrapbook. She befriended the vagabond mix of aviators and watched in horror as several of them were killed. Never once suggesting to her husband that he should quit such a dangerous occupation, Adelaide later wrote, “It isn’t a pleasure to know that your husband is flying a tricky exhibition monoplane when you fully realize what may be his fate any minute.”

In addition to huge prize money, it was not uncommon for aviators to receive an automobile or other lavish gift. Aviators accepted the risks and the rewards. Yet after anxiously waiting to see if her husband had survived a crash, Adelaide later wrote, “In a few seconds I lived an eternity.” Flying for money was exciting and lucrative. However, Adelaide privately questioned whether or not it was worth it.

High Stakes

The Ovingtons and Robinsons might have met at the Chicago International Air Meet in August 1911. “It was a great success,” wrote Adelaide, “because there were so many machines in the air at once and because there were so many accidents.”

Aviation historian Carroll F. Gray described the event, “in beautiful Grant Park, along the shore of Lake Michigan,” where huge crowds filled the mile-long grandstands to watch altitude, distance and duration records set daily. In all, Gray accounts for “34 aviators (including entrants from England, Poland, France and Germany) who competed for over $70,000 in prizes” [inflated to $1.6 million in 2013).

“The races I dreaded the most,” wrote Adelaide, “were out to the Crib and back. The Crib was a pile of rocks three miles out [in Lake Michigan]. A Curtiss flyer named Robinson, who flew a hydroaeroplane, spent most of his time picking wet aviators out of the lake.”

William “Billy” Badger’s fatal crash on the field was quickly followed by the drowning of St. Croix Johnstone, whom Robinson had attempted to rescue. Although he failed to reach Johnstone in time, he became the first to make an aircraft water rescue when he successfully plucked French aviator Rene Simon from Johnstone’s wreckage.

August was a busy month for Robinson. He earned FAI license No. 42 and made U.S. airmail history when authorized to deliver mail to six cities in Wisconsin, Iowa and Illinois, flying 375 miles.

Robinson was never a flashy stunt flier like Lincoln Beachey. As he gained experience with different weather conditions and air currents at varying altitudes, Robinson became increasingly safety conscious, refusing to fly when conditions were not acceptable to him. Nevertheless, Robinson had at least three serious injuries, including a broken collar bone after a crash in Wichita, KS. He walked away after crashes in the mud at Washington, D.C., and endured dunkings in the Columbia and Mississippi rivers. Robinson escaped injury but not embarrassment during a failed river landing in Germany. He also survived a more serious near-drowning in France after bad weather forced him down in 1912.

Although others had previously set records using regular aircraft, Robinson made several first flights between cities, over water and for altitude, speed and distance in a hydroaeroplane. By the end of 1911, he took a much-needed rest at home with his family. However, he was soon back in the air as a test pilot for Curtiss’s latest hydroaeroplane.

In early 1912, French aviator Louis Paulhan visited Curtiss’s hydroaeroplane factory in New York and contracted for the rights to sell the aircraft in France. He hired Robinson as his flying instructor and by April they were both participating in contests at Monte Carlo. That same year, Robinson briefly worked with Tom Benoist in Chicago, where they built a flying boat. Robinson then returned to work for Curtiss in New York.

Perhaps voicing what Estia might have felt about her husband’s exhibition flying, Adelaide wrote, “I might have enjoyed it, but because I happened to be an aviator’s wife, my nerves were tense every minute. I wonder if the processes of evolution will ever wipe out our primitive longing to witness suffering and death.”

Robinson worked several years as an engineer after retiring from exhibition flying. When Curtiss abandoned aviation in 1924 to develop a community in Florida, Robinson again accepted a job with his old friend, morphing seamlessly into the real-estate business. Robinson spent his last years in Maryland, where he died in 1963.

Exhibition aviator, Earle Ovington also escaped major injury and death, retiring to live in southern California. So it seems the number “13” may be lucky after all.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author who has received the DAR History Medal and Honorable Mention from the New York Book Festival. She has appeared on the History Channel and PBS documentaries. For further information visit her web site: www.GiaBKoontz.com.