Overcoming Conflict in the Workplace

Let’s discuss why events can escalate without us realizing it and how to get along when someone is being difficult, whether that someone is a colleague, crew member or part of our family. Recalling from my previous article, miscommunication occurs for several reasons:

1. The words used are ambiguous. Sometimes, usually, soon and even always and never mean different things to different people. OK can mean either “I heard what you said” or “I agree with what you said.” This can lead to one person expecting action or a response whereas the other person believes the conversation is complete.

2. Some people will share many details while others prefer the CliffsNotes version. Listening to details that seemingly have no relevance to the story or its outcome can raise impatience and cause frustration. Does it really matter if someone was 15 minutes late or 20?

3. The people who need to connect with others can spend more time in small talk conversations than those who are comfortable sharing only work details. Not acknowledging the other person can lead to worry, anxiety concern and a general lack of productivity.

4. Don’t assume that just because someone acted in a foolish or in an inappropriate manner (in your opinion) during the previous get together, they will act the same way this time. We might remember that last year, Joe came to work and took twice as long to complete his work because he was dreading going home to visitors. We will probably brace ourselves for the same type of behavior from Joe, and we can be guarded, wary or irritable. Who is to say that those visitors won’t be in town this year or that Joe has adjusted his attitude towards them? If we believe a family member judges our success against theirs (and their success includes more money, bigger house, newer car and other materialistic items), we are definitely doomed for an escalated discussion.

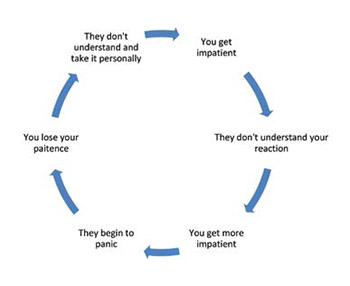

In each of these scenarios, our reaction to the situation is just as critical as the other person’s. The firing of defense mechanisms becomes contagious and feeds off the tension in the air. The circles on page 46 illustrate how a situation can easily get out of hand when a person does not understand the response process of another person. Our reactions (positive or negative) have an effect on others and they will react to our reactions. That’s how discussions become escalated and arguments ensue.

As we can see, these vicious circles are self-perpetuating. The longer this type of discussion continues, the greater chance of escalating into a situation that results in regrettable words being spewed and actions causing ill feelings. If it is in a work environment, it influences safety negatively and hampers collaboration. If it is in a home environment, it affects everyone attending the function. The present and future interactions are affected in both environments. After all, how can we be pleasant to someone who just embarrassed us, or rehashed a prior argument in front of other people?

These scenarios do not have to end badly or uncomfortably. It only takes one person to throw a wrench into this circle, to derail the path that each person’s brain is fixated upon. The key being aware enough of our triggers and of the situation to switch brains and break that chain.

Let’s talk a moment about our triggers. These are words, innuendos, behaviors or inferences that immediately take us from a cool, calm and collected mental state to one that can resemble a raving lunatic. Years ago, it was the word “whatever” coupled with a heavy sigh (either before or after) that immediately caused a person to retaliate. “Whatever” also included rolling of the eyes and/or a flippant hand wave with the same end result. “Talk to the hand” was another one that would set people off immediately. Ours can be words (“ok,” “it’s not my job,” “I did it last time,” “the manual/policy states …”), actions (raising eyebrows, shrugging shoulders, nodding head, pursing lips) or a combination of these actions and words. Knowing our triggers will allow us to prepare appropriate responses prior to them actually occurring. This can result in avoiding (not fleeing), overreacting to and diffusing a potentially distressing situation.

What can we do to end a potentially hazardous situation? There are several things we can do, depending on our involvement. There are two important points to remember that apply to all situations:

1. “Calm down,” “It’s not that bad,” or similar clichés only fuel the other person’s emotions. They have the exact opposite reaction. Think of how we feel when someone barks at us to “calm down” or patronizingly says “it really wasn’t that bad.” They interpret our response as minimizing their reaction (much like a parent can do with a child) or that we do not understand the severity of the situation. Either way, we are judging and chastising their reaction, much like calling them a name. The brain does not see a difference between a physical cut or bruise and a perceived attack.

2. We must acknowledge their reaction before moving on to the real reason for their behavior. This is not to say we agree with how they are feeling (dejected, anxious, angry, embarrassed); it only says that we can see they are upset and we want to help them work through understanding and accepting the situation. “Wow you are really upset about this. Let’s talk about it” or “You seem to be preoccupied or worried. What’s going on?” or similar words will let the other person know their unusual behaviors are obvious and we are willing to listen.

Now onto specific actions to take. Remember the communications circle from my previous article? People who are on the left side of the circle (disconnect) and in the upper half (in control) are more likely to attack and more vocally defend their position. Those who lie in the lower half of the circle (flexible) and on the right side (connect) will take a more retreating approach.

If we are the unsuspecting recipient of another’s outburst, we need to stop ourselves from getting sucked into their emotional sharkfest (see the circles to the left). We can do this by silently repeating a mantra (“this too shall pass,” “just a few more minutes and I can talk,” or something similar). This action takes our mind away from its perceived danger and allows us to maintain our composure. We shouldn’t back away from the person (that can make them more irate); instead, we should stand our ground. When they take a breath, ask “anything else?” That can catch them off guard and it gives them the opportunity to release their anger. If they accuse us of something and are correct, admit it. (Say something like “You are right, I did not listen to your complete explanation,” or “Yes, I did not do what I said I would”). Again, that will help diffuse their emotions and return their mindset to a more objective one with which we can have a calm discussion.

If we are the instigator, it is more difficult to separate our emotional reaction from our outward behaviors. We are in the attack, defend and survive mindset. We might not be aware of our surroundings, and initially we certainly are not aware of how we look to by-standers. To our brain, our actions are a result of a threat and we are taking action to live and fight another day. At some point, however, our rational brain will take over and we realize (a) we overreacted, (b) we were not correct, (c) we behaved like a raving lunatic, or (d) all of the above. If we are in the middle of our tirade and we realize the inappropriateness of our actions, we need to stop talking. Yes, we can stop mid-sentence or even mid-word. Chances are that most of the other people have already tuned us out. We can then turn and walk away, which can also include an apology for our actions. That is the most important step. The second-most-important step is to remove ourself from that physical location for at least 30 minutes. That is how long it takes for our mind to transition from “attack” to “all is well.” Our next interactions with those who witnessed our temper tantrum can be extremely tentative; we have lost some of their trust and respect. We must work twice as hard to gain it back.

Our behaviors are driven by our thoughts and our perceptions. When we interpret another’s actions as ones that will humiliate or embarrass us, impact our employment or cause us to lose respect from our colleagues, our brain will choose the fight or flight reaction. Stopping discussions from escalating into shouting matches is a conscious and high-energy activity, one that cannot be accomplished in a short timeframe. Raising our awareness of our own triggers and reactions, and noticing what aggravates our direct reports, can save us time, money and headaches.

Dr. Shari Frisinger’s human factors programs raise awareness of potentially disruptive or unsafe behaviors before they occur. This eases conflict, enhances safety and elevates service. Her clients want to improve their strategic decision-making thought process, implementation and results through emotional intelligence, team collaboration and individual accountability. For more information, visit www.ShariFrisinger.comor call (281) 992-4136.

Dr. Shari Frisinger’s human factors programs raise awareness of potentially disruptive or unsafe behaviors before they occur. This eases conflict, enhances safety and elevates service. Her clients want to improve their strategic decision-making thought process, implementation and results through emotional intelligence, team collaboration and individual accountability. For more information, visit www.ShariFrisinger.comor call (281) 992-4136.