J. Parker Van Zandt and The Big Ditch

By 1920, Arizona’s Grand Canyon was one of the original sixteen U.S. National Parks. Early visitors made the trip to the south rim of the canyon on foot, horse, mule or wagon, and later, by automobile over crude dirt roads. Then as now, rim views are of endless shades of tan and purple rock formations, and the olive green Colorado River which snakes through it. The enormity of this carved-out hole in the ground was left to the imagination until the invention of the airplane. From above, both sides of the canyon can be seen at the same time, dropping dramatically from flat land down miles of cliffs. Arizonans have nicknamed this natural wonder the Big Ditch.

Following the 1927 cross-Atlantic flight of Charles Lindbergh, flying gained popularity with the general public. But, regularly scheduled passenger flights, particularly for sightseeing was not yet common. That year, J. Parker Van Zandt [1894-1990] was working for the Stout All Metal Airplane Company on Henry Ford’s airfield in Detroit when a routine assignment led to a major change in his personal life as well as the future of tourism at the Grand Canyon.

Born in Illinois, Van Zandt was a natural mechanic who later graduated with a college degree in Engineering. During his WWI military service Van Zandt’s convoy encamped near a French air squadron where he was taken up in a flimsy “cloth and wood” aircraft. “That short ride gave me a new objective,” Van Zandt later wrote in his Memoirs, “All my efforts from then on were directed to trading my truck for an airplane.” Throughout 1918 Van Zandt lived in Paris, and was later transferred to England where he worked on radio navigation methods for bombing missions in “lumbering Handley Page bombers.”

Returning home after the Armistice, Van Zandt earned his pilot’s license at March Field near Riverside, California. By the spring of 1919 the Air Service assigned him to Mather Field, near Sacramento, California, flying air patrols to report forest fires. Van Zandt was eventually assigned to McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio, where he worked on a team which designed a compass that ignored metallic interference. The compass’ inventors were awarded the Magellan Medal in 1921, and in 1927 Charles Lindbergh used it to navigate his Spirit of St. Louis.

Returning home after the Armistice, Van Zandt earned his pilot’s license at March Field near Riverside, California. By the spring of 1919 the Air Service assigned him to Mather Field, near Sacramento, California, flying air patrols to report forest fires. Van Zandt was eventually assigned to McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio, where he worked on a team which designed a compass that ignored metallic interference. The compass’ inventors were awarded the Magellan Medal in 1921, and in 1927 Charles Lindbergh used it to navigate his Spirit of St. Louis.

From Capitol Hill to Red Butte

In 1926, Van Zandt was appointed the first Civil Aviation Advisor based in Washington, D.C. with a plan to integrate and encourage a civil aviation training program to support the military. The plan was three-pronged:

1) Create Federal legislation to support civil aviation and avoid State regulations;

2) Create Federal navigational aids for aviators as it already did for coastal shipping;

3) Expand the bidding for U.S. air mail routes to civilian carriers

By 1927, many of Van Zandt’s goals had been achieved, and he became restless. He wrote, “I never felt really at home in the military. Perhaps I was too independent-minded.” He resigned, keeping his Captain’s Commission in the Air Force Reserve. Immediately put to work by the Civil Aeronautics Administration to set up Federal licensing for aviators, Van Zandt issued himself Federal Pilot’s License Number 17. Soon thereafter he was hired by Henry Ford as Chief Pilot for the Ford Motor Company’s fledgling airline division headed by William “Bill” Stout. Van Zandt ferried Ford’s first all-metal Tri-Motor off the production line in Detroit to its owner in California. On this flight, Van Zandt would experience the thrill of flying over the Grand Canyon for the first time, at which moment he admitted feeling “the tug of the wild!”

When Grand Canyon vendors contacted Ford to use his Tri-Motors for air tours, Van Zandt eagerly accepted Stout’s assignment to negotiate a deal.

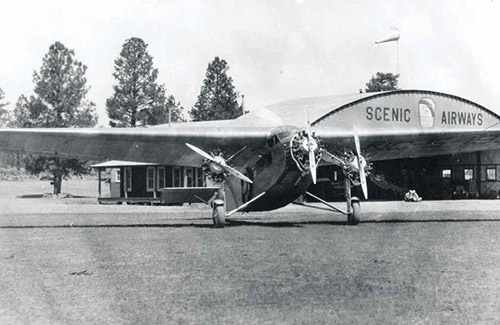

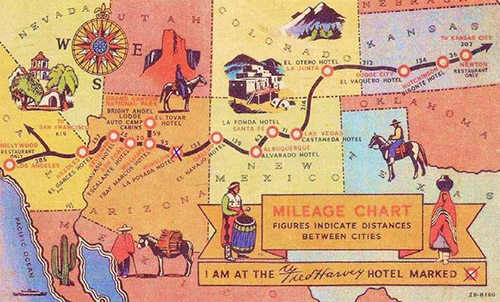

At the canyon, Van Zandt cemented an alliance with the Fred Harvey hotel and restaurant chain, already well established at the canyon’s south rim. From the National Park Service (NPS), he secured a lease on an 800-acre meadow about fifteen miles south of the canyon rim for his aerodrome. Back in Detroit, Van Zandt quickly formed Scenic Airways, Inc., with Stout and six additional financiers, including Eleanor Roosevelt’s brother, C. Hall Roosevelt. Within weeks Van Zandt hired airport architect, Russell B. Shaw, to design a passenger terminal attached to a hangar large enough for the wing span of a Ford Tri-Motor, plus maintenance equipment.

Van Zandt’s aerodrome was at the base of Red Butte, a lone hump of earth on miles of forested, flat land inhabited by prairie dogs, rattlesnakes and elk. Within months Scenic had a runway several thousand feet long, a remarkably modern hangar, a comfortable lobby for tourists, four employee residences, and several out-buildings equipped with running water and electricity. Miles from the nearest townships, railhead, or smooth paved highway, Shaw’s construction crews transported materials by truck over crude dirt roads.

Before Scenic’s aircraft were regularly filled with tourists over the canyon Van Zandt took hunting parties, NPS employees and adventuresome travelers almost anywhere he could find a flat place to land his Stinson Detroiter. Van Zandt summarized his concept, construction, operation and ultimate Depression Era business losses in his Memoirs, written in 1984. At age 90, his backward glance was brief, but not without detail,

“…In the spring of 1928, we bought two Tri-Motors at $85,000 apiece and started sight-seeing flights over the Grand Canyon and elsewhere in the Southwest. We carried “Hosteen” John Wetherill, noted guide and discoverer of Mesa Verde ruins, on one ninety minute flight over Rainbow Natural Bridge, and the Painted Desert, and landed him back in front of his home in Monument Valley. It had taken him, he said, two weeks by pack train, the last time he had covered that route!”

Business was great all during the summer tourist season at the Canyon. In anticipation of the winter lull, we had set up a training school and built an airfield at Phoenix, Arizona. We named it Sky Harbor. We had ambitious plans to merge Scenic Airways with aviation operations elsewhere and raised twenty million dollars in pledges from Chicago and Detroit financiers.”

Van Zandt’s plan for air tours in other National Parks was short-lived when Scenic became a casualty of the Great Depression in 1929. “Our promised funds vanished,” wrote Van Zandt. We sold Scenic Airways to a local operator; and I returned to Detroit.” Ford then shipped Van Zandt and a crew with a “knocked-down Tri-Motor” across the Atlantic.

Belly-Dancers and Sword-Swallowers

In 1929, Van Zandt, pilot Roy Manning, and mechanic, Carl Wenzel, exhibited the Tri-Motor in 21 countries. They sold a plane to the government of Czechoslovakia, and another to Spanish Airways. Just as Van Zandt began to train the Spanish aviators in their new aircraft, the Junkers Company, which also built metal airplanes, filed a lawsuit against Ford. Although Ford eventually prevailed, he decided not to risk further problems and brought Van Zandt home.

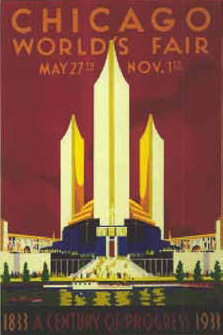

With his wanderlust temporarily satisfied, Van Zandt moved to Chicago, Illinois, to be near relatives who were then working in high positions on the World’s Fair of 1933.

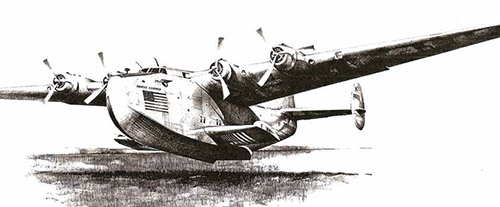

Originally hired to organize automotive and aviation exhibits at the Fair, Van Zandt was sent to Europe and the Middle East to recruit foreign exhibitors. He brought back belly dancers, snake-charmers and sword-swallowers, who became the hit of the Midway. A year later Juan Trippe, President of Pan American Airways, hired Van Zandt as PAA’s first Airport Manager in Hawaii.

The rest of Van Zandt’s remarkable life includes his wife, Lydia, by his side during adventures all over the world. He retired to become an active member of his California coastal community. In 1978 he visited the Grand Canyon where he met with air tour operators who had followed in his footsteps and considered him a living legend. J. Parker Van Zandt, the father of sight-seeing over the Grand Canyon died in 1990 at age 96.

Today hundreds of air tours in both fixed wing and helicopters carry thousands of passengers above the Colorado River and over the canyon’s landmarks. Noise abatements and other environmental concerns are now imposed, but for the most part air tourism over the Big Ditch is exactly as Van Zandt had envision.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author who has received the DAR History Medal and Honorable Mention from the New York Book Festival. She has appeared on the History Channel and in PBS documentaries. For more information, visit www.GiaBKoontz.com.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author who has received the DAR History Medal and Honorable Mention from the New York Book Festival. She has appeared on the History Channel and in PBS documentaries. For more information, visit www.GiaBKoontz.com.