THE GREAT MERGER TAT, Part Three of Three

Since its inaugural flights in July 1929, Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT) had dazzled its coast-to-coast passengers with stunning airport lounges, meticulous meal service by restauranteur Fred Harvey, and comfortable Aerocar coach transportation between train and aircraft. Canopied walkways shielded travelers from wind or rain between the terminal and aircraft. Special Pullman cars were appointed with dining and sleeping options and the ever-present personal service of a steward. In the air, male “couriers” served meals on folding tables appointed with table linens and specially-designed china and flatware. A cross-country one-way ticket was about $350 and life insurance could be added for a reasonable fee.

Offering life insurance probably added skepticism for those already reluctant to travel by air. Countering with reassurances, TAT officials boasted that, “Never has an airline presented such public service and thorough preparation and adequate equipment.” However, after just three months in operation, TAT suffered the first in a series of accidents that changed its future.

On Sept. 3, 1929, TAT’s westbound flight from Albuquerque, NM, to Winslow, AZ, its Ford Trimotor, “The City of San Francisco,” entered a violent storm and diverted its course over Mt. Taylor near Grants, NM.

“That morning,” writes aviation archaeologist Steve Owen, “the flight simply vanished without a trace.” The crew of three, plus five passengers, all perished. TAT temporarily suspended flights and some feared it was the end of all commercial passenger air travel. But TAT resumed with optimism, and more complimentary advertising. It is likely few people ever knew the details of the disaster, as the Bureau of Air Commerce (then in charge of investigating accidents) had a policy of non-disclosure. In 2009, Owen and other professional investigators surveyed the crash site.

“Eighty years after the crash,” writes Owen, “trunks of trees hit by the TAT Trimotor as it went down were still identifiable.”

The Flight of the Condor

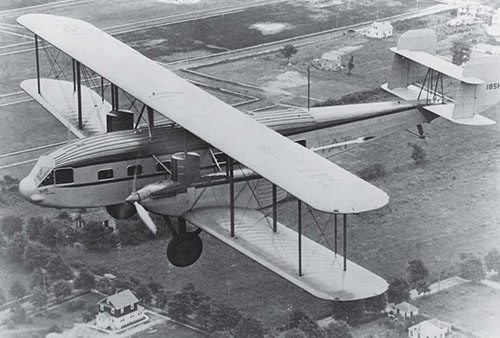

Projecting continued growth, TAT added two Curtiss Condor aircraft to its Eastern Division fleet. In an article for Air Travel News published during November 1929, passenger Arthur Phillips described his trip from St. Louis to Glendale, CA. Phillips was one of 12 passengers on a new 18-passenger Condor which had a wing span of 91 feet and was powered by two 600hp Curtiss Conqueror engines. Phillips describes a smooth ride, even as he flew through a driving rainstorm, enjoying his “delicious repast” of roast chicken while seated in “the dark green, deeply-upholstered leather chair with adjustable reclining back.” The mauve-colored cloth walls of the cabin were “efficiently insulated, which zealously protected the passengers from all traces of vibration and reduced the roar of the motors to a gentle purring.” The cabin was appointed with “easily-opened windows and neatly-arranged lights.” Those new to air travel were mesmerized by the sight of cloud formations through their windows and great rivers which looked like unraveled thread from a patchwork quilt of farms thousands of feet below.

Phillips’ trip included a brief stop at Kansas City for TAT maintenance to add gas, oil and water to the huge aircraft.

“Five hundred people crowded around the plane,” writes Phillips, “for this was the first time a Condor had been in Kansas City.” With no reason to stop at TAT’s airport in Wichita, KS, the flight ended for the day at Oklahoma’s Waynoka airport, which Phillips noted was “alone in the center of a vast expanse of prairies.” From Waynoka, Phillips traveled to Clovis, NM, via the Santa Fe railroad.

From Clovis, the rest of the journey was aboard a Ford Trimotor, “The City of Wichita,” which stopped for service in Albuquerque. Here, the pilots disappeared into a small radio shack where they reviewed the latest weather reports. These updates were also available during flight, received through an eight-foot mast on the roof of the aircraft. Once aloft, transmissions were sent via the unwound 100-foot trailing antenna. From Albuquerque, the western landscape must have looked as desolate as the moon for those accustomed to leafy green forests and fields. From 10,000 feet, the expanse of desert plateaus, dramatic mesas and the meteor crater gave way to vast canyons, giant rocks, and the colorful sands of the Painted Desert.

The fatal crash in September must surely have entered Phillips’ mind as he landed at Winslow during a driving rain, but his article for Air Travel News mentions only the terminal’s “cheerful log fire.” Phillips continued by train and plane over the Colorado River, the Mojave Desert, the High Sierra, the orchards of southern California and finally, the city scene at Glendale. Phillips’ glowing travel journal had barely reached the hands of readers, when on Dec. 23, TAT’s eastbound flight from St. Louis to Columbus, OH, made a crash landing in a snow storm at the airport at Indianapolis. Of the 11 on board, one passenger was killed. Although the story was carried in newspapers across the U.S., the Bureau of Air Commerce did not release official details to the public.

Tragedy, Bureaucracy and Success

During the last months of 1929, TAT merged with Maddux Airlines, from whom they had already hired crew with experience flying Ford Trimotors. By January 1930, TAT offered side trips between the border town of Tijuana, Mexico, and Glendale, CA, for a day of horse racing at Agua Caliente. On Jan. 19, the northbound TAT-Maddux Ford Trimotor crashed during a rainstorm along the foggy California coast. Fourteen passengers and two crew members were killed.

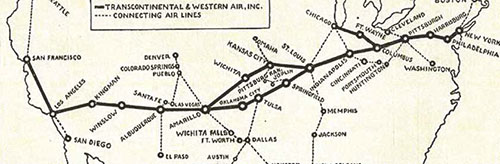

Remarkable as it seems, TAT-Maddux continued regular operations, even as public awareness of air disasters increased. Meanwhile, U.S. Postmaster, Gen. Walter Folger, urged Western Air Express (WAE), which held contracts to fly mail from Utah to California, to merge with TAT-Maddox. On July 16, 1930, TAT and Western Air formed Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA). In the summer of 1931, TWA moved its headquarters to Kansas City, MO, and was eventually headed by Jack Frye.

TAT’s operation standards were the basis for several of the USA’s largest airports and commercial airlines. In its short history, TAT safely transported thousands of passengers. The public was not given details by the Bureau of Air Commerce of TAT’s accidents between 1929 and 1930, which claimed 25 lives. On Sept. 3, 1929, TAT’s eastbound flight out of Los Angeles carried famous actress Delores Del Rio. Owen speculated that had Del Rio been aboard the fatal TAT westbound flight, “it may have caused a bigger impact on authorities,” to change the Bureau’s policy of non-disclosure. Eighteen months later, famous Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne was among the eight fatalities after a TWA Fokker Trimotor crashed in a Kansas wheat field on March 31, 1931. President Roosevelt and the American public demanded details of the accident, forcing the Bureau to reverse its policy of secrecy.

In 1958, the Federal Aviation Authority took over the responsibilities of the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) and the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), eventually becoming the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Today’s FAA makes public the results of its accident investigations.

During the Golden Age of Aviation while TAT morphed into TWA, general aviation fatal accidents were not uncommon. However, there were great survival stories, too. One has to wonder how officials would have described the crash on Sept. 16, 1927, of a Ryan Braugham piloted by famed aviator Martin Jensen in the forests near Payson, AZ.

While flying the Ryan, Jensen lost control of his aircraft carrying Leo, the MGM lion, from Santa Monica, CA, to New York for a publicity stunt. Both Jensen and Leo survived the crash, and, with help from local ranch hands, Leo was safely transported back to Hollywood, where he lived a long (and tame) life.

Now you know why the iconic MGM lion roars triumphantly at the beginning of an old movie.