THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL AVIATORS

Between August and November 1907, Orville and Wilbur Wright traveled to Europe to secure contracts with the French and German governments for the purchase of their aircraft. On the chance that a demonstration flight was required to convince their customers, and also to confine the secrets of their invention, they brought along Charles Edward Taylor, their mechanic. Refusing to reveal their flying machine before contracts were signed, Taylor’s responsibilities were confined to packing tools and parts for shipment between the U.S. and Europe. The Wrights did little to refute the claims that they were frauds. Nevertheless, in 1908, Wilbur returned to France and stunned the world with the maneuverability of his Flyer. The following spring, Taylor joined the Wrights during several intense weeks of flying in Europe. The French quipped that “The Wright Brothers made a glider. Charles Taylor made the glider an aeroplane.” More than 100 years later, proud Americans honor Taylor on his birthday, May 24 — Aviation Maintenance Technician Day.

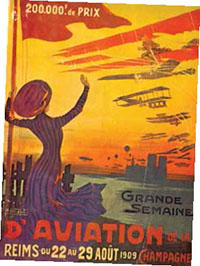

Flying the monoplane he designed, Frenchman Louis Bleriot crossed the English Channel in July 1909. Within weeks, he represented his country at Rheims when France hosted the world’s first great air meet. A month later, the International Exposition of Aerial Locomotion opened in Paris at the Grand Palais. Giant balloons reached the ceiling of the salon above exhibits for new inventions of aircraft, engines, propellers and an array of instruments. At the time, France dominated the advancement of aviation, but among the few foreign designs was a Wright Flyer. The popular exhibition was soon followed by international air meets in Italy, Germany, England, Egypt, Belgium, the U.S. and France. Several competitions were held for altitude, distance and speed.

In the years between 1903 and 1910, the first aviator to fly over a lake, a city, a bridge, or mountain became a celebrity. The first to fly in each country was an honor often achieved by a foreigner using a French or American machine. On Feb. 10, 1910, Capt. Paul Engelhardt of Germany was the first to fly in Switzerland and he used a Wright machine. Three months later, Ernest Failloubaz made the first flight in Switzerland of an aircraft built and piloted by a Swiss citizen. Six months and several exhibition flights later, he became Switzerland’s first licensed pilot at age 18.

In 1906, Brazilian native Alberto Santos-Dumont became the first fly in France. That same year, while living in Paris, Romania’s Trajan Vuia flew an aircraft of his own design. In 1909, Bleriot made the first flights in both Rumania and Hungary. Aviation record books are careful to distinguish between the first person to fly in a country and the first native countryman to design, build and fly his own machine.

In Australia, for example, John R. Diegan and his brother Reginald were the first in their country to design and build the plane that John flew in 1910 near Mia Mia, Victoria. The first Englishman to achieve a similar honor was Edwin Alliott Verdon Roe (A.V. Roe) who designed a tri-plane which he flew in 1909 at Walthamstow Marshes.

Nevertheless, two Americans briefly and literally stole the spotlight from Diegan and Roe.

The Cowboy and the Magician

Before silent films arrived in the 1920s, the melodrama and mystery of live theater captivated audiences around the world. Two of the most famous stars of the day were magician Harry Houdini [1874-1926] and Wild West sharpshooter Samuel F. Cody [1861-1913].

Before silent films arrived in the 1920s, the melodrama and mystery of live theater captivated audiences around the world. Two of the most famous stars of the day were magician Harry Houdini [1874-1926] and Wild West sharpshooter Samuel F. Cody [1861-1913].

Born Ehrich Weiss in Hungary, Houdini immigrated to the U.S. at the age of four, gaining U.S. citizenship through his father. He performed a trapeze act as “Ehrich, Prince of the Air” by age nine. Eventually, as Houdini, he became a popular professional magician, famous for his escapes from chains, handcuffs and sealed boxes. He mystified audiences around the world with his illusions.

Like Houdini, Midwestern cowboy Samuel Franklin Cowdery changed his name when he quit being a cowboy and joined a Wild West show. As “S.F. Cody,” he falsely billed himself as a descendent of William F. Cody [1846-1917], the famous soldier, buffalo hunter and creator of “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West” traveling show. Like his predecessor, Cody was a precision marksman and horseman. On tour in Europe, Cody challenged (and won) races on horseback against English and French bicyclists. No stunt was  too far fetched if it meant prize money. He was inventive and fearless.

too far fetched if it meant prize money. He was inventive and fearless.

“Work Will Do It”

Cody became interested in kites while performing in England in1899. He ascertained they would be entertaining and useful transportation. French and English tabloids chronicled his one-man, kite-propelled boat trip across the English Channel in 1903. It took 13 hours. More successful was what Cody called the “man-lifting-kite,” a clever series of stabilizing kites attached by a cable to a huge “pilot kite” soaring 300 feet above. Seated in a basket attached by a pulley system, Cody “flew” into the air. His kite experiments elicited great interest from Great Britain’s “War Balloon Factory.” Cody quit the stage and worked full time for the rest of his life, developing military observation kites and, beginning in 1907, a series of successful aeroplanes.

Eventually Cody built a biplane with a four-cylinder Antoinette engine which he flew on Oct. 16, 1908, at Farnborough Common, England. He was the first person to fly an aeroplane in the U.K.

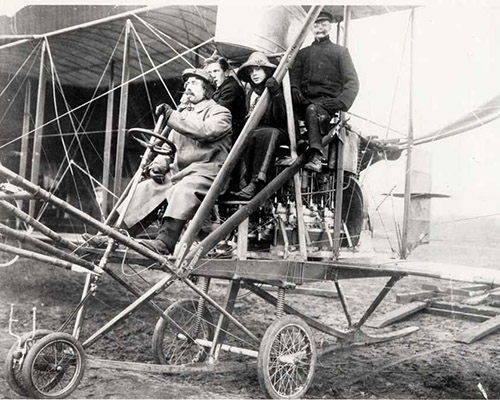

He became a citizen of Great Britain in order to represent England in subsequent air meets and races. Between 1908 and 1913, Cody developed several different aeroplanes using a variety of engines. Outclassing smaller, faster aircraft, his “Flying Cathedral” (Cody No. 1C) could carry multiple passengers and stay aloft for hours.

Large companies like Hanriot and Deperdussin hired well-paid, famous aviators and employed dozens of mechanics and assistants. These were Cody’s competition for prize money and military aircraft contracts.

By contrast, Cody worked alone, designing, building and testing. He had a few loyal volunteers who followed his directions even when a task seemed impossible. Cody instilled confidence in those who worked with him, frequently repeating his favorite motto, “Work will do it.” Often critically injured and suffering financial hardship, Cody was relentless and indefatigable.

Through his hardships, Cody won the hearts of his adopted countrymen and the respect of fellow aviators. After a lifetime of struggling, his future finally seemed secure as Her Majesty’s War Office chose his Cathedral design for service by in 1913.

Both Cody and his passenger were killed that August during a routine flight on England’s Laffins’ Plain. King George V published condolences to his nation, extolling his friend’s “dogged determination and dauntless courage.” Quickly eclipsed by military aircraft developed for WWI, Cody’s aeroplanes were never produced, but he is rightfully credited with awakening English air-mindedness.

Up at Diggers Rest

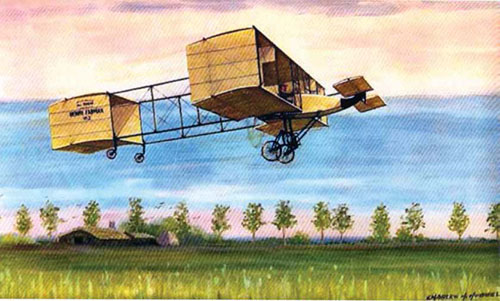

Advances in the magical phenomenon of flight also intrigued Houdini. He purchased a French Voisin bi-plane while in Europe in 1909. With little instruction, he learned to fly and painted his name in huge block letters across the Voisin’s fuselage and tail. In 1910, he had the aircraft shipped to Australia where he was scheduled to perform in Melbourne.

Advances in the magical phenomenon of flight also intrigued Houdini. He purchased a French Voisin bi-plane while in Europe in 1909. With little instruction, he learned to fly and painted his name in huge block letters across the Voisin’s fuselage and tail. In 1910, he had the aircraft shipped to Australia where he was scheduled to perform in Melbourne.

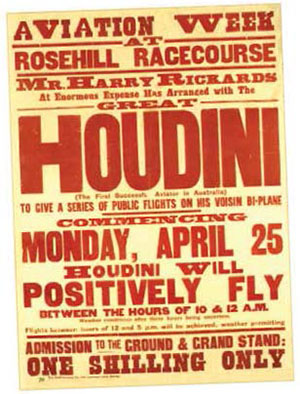

On March 18, 1910, about 20 miles north of Melbourne at Diggers Rest, Houdini took the controls and made three short but well-executed flights, thus becoming the first to fly an aeroplane in Australia. Three days later, he stayed aloft for seven minutes. He made exhibition flights in the proximity of Sydney at Rosehill in April 1910.

Upon Houdini’s return to England, he placed his Voisin in storage and never flew again. He died of acute appendicitis in Michigan on Oct. 31, 1926. He is honored annually by the American “Broken Wand Society.”

Both Cody and Houdini had a flair for the overdramatic, often bragging of success before it had been won. Yet, as fliers, they were uncharacteristically subdued. Accolades from their fellow fliers and an adoring public were based upon merit rather than rhetoric. Houdini is said to have taken his lead from Wilbur Wright, who wasn’t much of a talker, and disliked giving speeches. He once said, “I only know of one bird, the parrot, that talks, and he can’t fly very high.

“We are the bird-men,” Houdini said, “and I wouldn’t like Wilbur Wright to class me as a parrot.”

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author who has received the DAR History Medal and Honorable Mention from the New York Book Festival. She has appeared on the History Channel and PBS documentaries. For more information, visit www.GiaBKoontz.com.