Did You Ever Get Stung By A Dead Bee?

This was iterated by Walter Brennan in the Humphrey Bogart movie “To Have or Have Not.” I don’t remember what he was getting at in the movie, but I mention it here because it appears that the things that we regard as inconsequential and won’t harm us wind up biting us in the rear.

We may intentionally disregard certain things (and that is another matter) but what interest me are the things that we disregard because we subconsciously don’t see them. This isn’t some kind of voodoo hypnotism mumbo jumbo — it is cognitive blindness. Your eyes see but your mind doesn’t register. It is actually registering but your mind has this tendency to try to make things organized — but reality is not an organized event. This has our mind arranging things as they actually aren’t, adding things that are not there, and removing things that are there. Our mind seeks to make order of chaos, but chaos is the norm.

How many have missed something during an inspection and after someone points it out you say to yourself, “How could I have missed that?” Have you ever been so focused on a task that you failed to see what is occurring around you? Conversely, have you been so absorbed in taking in the big picture that details fall by the way side? We have this unflappable ability to detect the minutia and miss the obvious, and see the obvious but overlook the details. We are also capable of calmly conducting complicated tasks and get frustrated over menial ones.

You’re not going crazy. This is human nature. No matter what your colleagues tell you, you’re also not inept or incompetent. That’s just someone who is incapable of making his/her own light shine bright, so they do the next best thing to make them stand out: they dim your light.

Cognitive blindness factors

We experience cognitive blindness due to a number of factors like being too macro focused or too micro focused. In either case, awareness of our surroundings is imperative. Awareness is one of the infamous dirty dozen so you will see the linkage how awareness can overcome some cognitive blindness. Awareness comes through experience and training, therefore you have to rely on your learning to overcome these issues. If you aren’t trained in a task, it’s frustrating for you to try to accomplish it whereas someone who has had the training find it easy. Frustration breeds mistakes which breed more frustration, and so on down the line.

If you are a pilot, you have experienced cognitive blindness and your mind trying to make order of chaos. When you started your instrument training the instructor probably had you try to control the aircraft with a hood on and instruments blanked out. You had to control level flight by your instinct alone, no external references. For most of us, this did not have a favorable result. As we learned to rely on our instruments, we had to fight the inner urge to do something else (but this dissipates over time). “Rely on your instruments,” said the instructor and so it is in life also. We rely on our learning but the difficulty is that the mind has such a strong influence on us that we will always see it a little differently than it actually is.

Examples

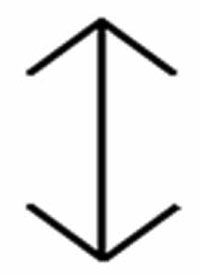

To illustrate this, look at the Muller-Lyer illusion to the left. If you’re not familiar with this, both vertical lines are the same length. Measure them if you don’t believe me. Even armed with that information, your mind does not register this fact and will continue to see them as different lengths. Your mind has placed such doubt in the way that you will always be compelled to measure the length to be sure even when your knowledge is telling you otherwise. Take away the arrows and your eyes and your mind will be in agreement that the two vertical lines are identical.

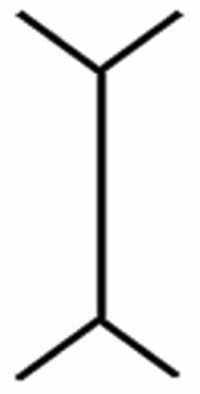

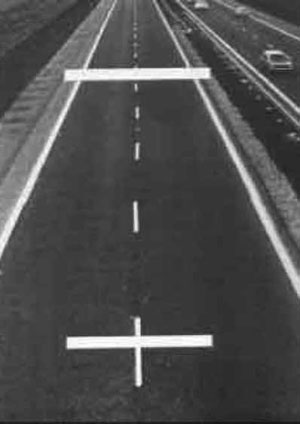

Perspective also drives our mind to see differently as both horizontal lines below are the same width. Our mind tries to adjust for distance, knowing that objects that are further away are smaller so it organizes the perspective. Your mind knows perspective enough that the road is the same width just further away. So since the upper line extends beyond the outer edges of the road and the lower line does not, then the upper line must be wider. Your mind sees the lines on the road as three-dimensional reality, not as the two-dimensional picture it is. The mind is trying to make things orderly by putting the lines in reality rather than in the picture, which is a replication of reality. Take away the road and we could easily see that the two lines are the same width; our mind readjusts to a two-dimensional reality.

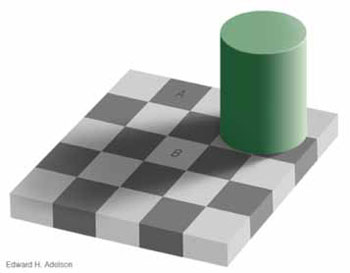

Our mind also tries to make sense out of shades and colors. I am not going into the color bias here but look at the figure on the next page and note square A and square B. If I told you they were the same shade, would you believe me? Probably not. Again, the mind will try to make order of the scene. Since square B is lighter than the surrounding squares and those surrounding squares appear to be the same shade as square A, then A must be darker than B. This may sound like some algebra problem form high school, but it is the mind’s logic which just deceived us. Fold this page so the two squares intersect. Amazing, isn’t it? As with the arrow and lines and even with prior knowledge, you will look at this figure and swear that the two are different. I even know what’s happening and I had to print it to see they were actually the same.

Cognitive awareness

The opposite of cognitive blindness is cognitive awareness. This should be our natural state. We are animals of nature and we possess certain awareness traits. We are attracted by anomalies and are thus distracted by movement when there should be none and stillness when there should be movement. We concentrate on the person who is talking to us but our eyes will divert to something moving in the background because we are spatially aware of our surroundings. During a busy basketball game, our attention would be drawn to the player that is not moving and just standing in the middle of the court. This is another dirty dozen factor: distraction. Magicians use this to perform slight-of-hand tricks and they call it diversion. They divert your attention away from the manipulation.

Watch a cat as it begins to stalk. It’s looking around to see what else to pounce on, a better target, or if there is something going to pounce on them. Once they choose their victim, they become totally concentrated on that object and will not remove their gaze from the prey. If you have ever watched a lion attacking its prey, the body moves and steers but the head remains totally fixated on the target. Their focus has moved from a wide panoramic view, taking in all available input data to enrich their choice or possible alternatives, then to a narrow view where all distraction is blocked out. They both have their place and time and they both have their advantages and disadvantages. You can distract the cat when they are in the wide view, but once they are committed they take on a narrow view and peripheral vision is impaired.

This is the problem with cell phone use and driving. There is a lot going on while we are driving and a lot we have to do as drivers. It has become second nature for most of us and we can go through life with no accidents or traffic tickets as we have learned to be spatially and cognitively aware of our surroundings. But throw in the cell phone and our focus starts to narrow on the phone and we lose track of some of those awareness abilities that we should possess as drivers. The same concept precipitated the sterile cockpit rule. Reduce distraction.

Should we have a sterile hangar floor rule where a technician working on a critical aircraft repair must only have conversation related to the task at hand? That might be something in the future but we aren’t ready for that yet. It still would be prudent to let the technician(s) do their job without distraction. But how many times have you been working on a complicated repair to get pulled off to help someone else, sign some piece of paper, or just asked a nonrelated question that sends you off track? Then you return to the task and try to pick up where you left off or where you think you left off. Did you inadvertently skip a step by doing so? Is that the old O-ring on the bench or the new O-ring? Those diversions are the norm and it has been suggested that when you return to the task, go three steps back in the work instructions. This all sounds good but reality comes into play and you have a supervisor yelling at you that you are deliberately slowing work production by repeating things you already did.

Do the safe thing

What is one to do? Do the safe thing and take your lumps from your boss. This is easier said than done, but I’m open if anyone has another suggestion. As we rush to do a job or begin to have self-doubt because we lack knowledge or are not confident we accomplished all the tasks, we will shed details to complete the task on time. Use the old carpenters axiom: “measure twice, cut once.”

Your mind will trick you. If it looks like a duck and sounds like a duck, it still may not be a duck. The job will distract you, so get back in focus and backtrack as needed. Your boss will rush you but don’t work beyond your capabilities. These all sound reasonable on paper but implementation is another matter. What we believe is right might not be; what we see as appropriate might not be either. This is why we have checklists, maintenance manuals and instructions. They are not infallible so don’t let a dead bee bite you.

Patrick Kinane joined the Air Force after high school and has worked in aviation since 1964. Kinane is a certified A&P with Inspection Authorization and also holds an FAA license and commercial pilot certificate with instrument rating. He earned a B.S. in aviation maintenance management, MBA in quantitative methods, M.S. in education and Ph.D. in organizational psychology. The majority of his aviation career has been involved with 121 carriers where he has held positions from aircraft mechanic to director of maintenance. Kinane currently works as Senior Quality Systems Auditor for AAR Corp. and adjunct professor for DeVry University instructing in Organizational Behavior, Total Quality Management (TQM) and Critical Thinking. PlaneQA is his consulting company that specializes in quality and safety system audits and training. Speaking engagements are available with subjects in Critical Thinking, Quality Systems and Organizational Behavior. For more information, visit www.PlaneQA.com.

Patrick Kinane joined the Air Force after high school and has worked in aviation since 1964. Kinane is a certified A&P with Inspection Authorization and also holds an FAA license and commercial pilot certificate with instrument rating. He earned a B.S. in aviation maintenance management, MBA in quantitative methods, M.S. in education and Ph.D. in organizational psychology. The majority of his aviation career has been involved with 121 carriers where he has held positions from aircraft mechanic to director of maintenance. Kinane currently works as Senior Quality Systems Auditor for AAR Corp. and adjunct professor for DeVry University instructing in Organizational Behavior, Total Quality Management (TQM) and Critical Thinking. PlaneQA is his consulting company that specializes in quality and safety system audits and training. Speaking engagements are available with subjects in Critical Thinking, Quality Systems and Organizational Behavior. For more information, visit www.PlaneQA.com.