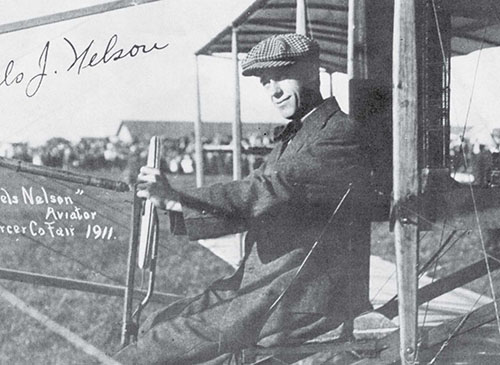

The Big Splashes of Nels J. Nelson

It was supposed to be a short exhibition flight over the bay to thrill spectators on the shore near Pensacola, FL. At the controls of the Curtiss-type aircraft he had constructed himself was Nels Nelson (1886-1964), who was on tour during December 1911. No loops, dips or spirals from high altitude were expected from the flier known for his crowd-pleasing level passes overhead — yet even those who had never before seen an aircraft knew the sputtering engine and sudden nose-down attitude meant disaster. Nelson struggled for control as his aircraft lost altitude, belly-flopped across the water, settled and sank. The crowd was stunned and frightened until Nelson was spotted splashing above the wreck. Both Nelson and his water-soaked aircraft were quickly dragged ashore. Neither flier nor his machine were badly damaged, and by late afternoon were again overhead thrilling the crowd. At his shop in New Britain, CT, Nelson was building a new aircraft designed with pontoons as alternate landing gear six months later.

The Natural “Builder”

Born in Sweden, Nelson and his family immigrated to New York when he was in grammar school, but soon moved to New Britain. The young and good-looking man who did not smoke or drink alcohol was known as a serious student. By 1909, he was a tool maker for the Stanley Rule and Level Co. (later to become Stanley Tools), adding income repairing motorcycles and automobiles. Caught up in America’s new “air-mindedness,” Nelson first built a glider. In 1910, he invented a four-cylinder engine for an aircraft of his own design.

In 1928, he was listed in Who’s Who in Aeronautics, but it is difficult to find Nelson’s name in most aviation history publications. However, he is not forgotten in Plainville, CT, where he was honored during the 100th anniversary of Robinson Airport. Plainville’s officials boasted that it was on their airport’s original grass strip that Nelson made his first flight in May 1911 when he was 21 years old. Aviators like Nelson were self-taught and flying before they took lessons from a pro or bothered to obtain their license, as he did in 1912, making him an “Early Bird.” Unlike his flashy, dare-devil peers, Nelson eschewed stunts and preferred simple demonstration flights. Nevertheless, his caution did not prevent him from accidents while appearing in a dozen midwest and southern states between 1911 and 1914. He was never badly injured and his conservative flying might have accounted for his remarkable longevity.

Nelson designed, constructed and flew seven biplanes similar to those manufactured by Glenn Curtiss. None of Nelson’s aircraft had fancy names and historians are left with identifying them in the order in which they were built, beginning with “Number One” in 1910 and ending with “Number Seven” in 1914.

He once said of his designs, “Build

it light and build it strong so it won’t come apart.”

Most survived to be sold, but a shop fire consumed one of Nelson’s aircraft and a second was blown to pieces during a wind storm.

At New Britain, Nelson supervised helpers eager to test his new machines. One historian describes the following method used by his crew on “Number Two” (in 1911) as “common for pilots of the day.”

The airplane was backed up to a convenient fence post and a rope or wire made fast to the plane’s tail or landing gear. An ordinary spring-type scale, such as was used for weighing blocks of ice, was tied between the rope to the landing gear and the other rope which was fastened to the fence post. The engine was started and run at full power. The amount the airplane pulled against the fence post was measured on the scale. A 50 horsepower engine, for instance, was supposed to develop a thrust of about 200 pounds. The rule of thumb called for a thrust of four pounds for each engine horsepower if the engine was functioning properly.

A small number of fliers traveled with their families, but Nelson appears to have been alone on the circuit. Nevertheless, he earned long-term friendships, hands-on assistance and occasional financial backing from those who had faith in his projects. This included Alex W. Stanley, founder of Stanley Rule and Level Co., and Aaron Cohen, owner of Cohen Motor Company, both of New Britain.

Exhibitions and the “Duel” with Hamilton

Between September and December 1911, Nelson toured the midwest and south representing the Chicago-based Mills Exhibition Company. Often without assistance, Nelson disassembled and packed his aircraft in crates for transport by train between towns. Upon arrival he uncrated, reassembled and tested his machine, sometime minutes before his public flight. Without grandstanding, Nelson was a crowd pleaser who had his moments of terror as well as fun. During the summer of 1912, Nelson flew an “unscheduled race” across the Mississippi River with famous French aviator Didier Masson, and also created a rare event in Connecticut aviation history.

Directly opposite to Nelson’s flying style was Charles K. Hamilton, a Connecticut aviator who was dubbed the “Demon of the Air” due to his daredevil stunts. Hamilton’s unruly red hair matched the myth of hot-headed personalities, as he was in constant conflict with family, employers and friends. In July 1912, Hamilton and Nelson were both in New Britain and short of funds. For immediate income, they organized a two-day “duel in the sky” to be held at the city’s fair grounds. A mutual friend agreed to act as monitor and judge. The contest was advertised heavily as a rivalry and more than 13,000 people paid 25 cents to witness the “greatest contest ever seen in the New England states.” Trading the lead in points for “fast start,” “spot landing” and other maneuvers, the contest ended in a draw. Both fliers walked away with $2,000 (which would have equalled $47,000 in 2012) and a smile.

“The whole thing was rigged,” wrote Hamilton’s biographer, John Sipple, “and they split the money evenly. Afterward Hamilton drove through New Britain swinging his money bag over his head.”

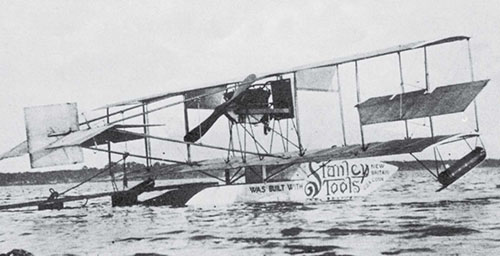

Nelson’s “Number Five” was a two-place, single-engine flying boat with a 75hp Roberts engine which he successfully tested on the Connecticut River, generating engagements for the 1913 flying season. With great confidence in his latest invention, Nelson accepted a lucrative exhibition contract in Rhode Island. His success was short-lived, however, when a wing dipped into a briny wave and caused a crash in which Nelson was again left splashing amid aircraft parts. Nelson was not badly hurt, but all he could salvage of his flying boat was the Roberts engine. Undaunted, but through with dunkings, Nelson next used the Roberts engine to build a biplane which he flew over solid ground in Wisconsin during the summer of 1913.

That winter, Owens hired Nelson to build an exhibition biplane which prudently included an optional float when a seaplane landing was required. Stanley paid Nelson to paint “Stanley Tools” on the pontoons of his machine while he toured Florida, Connecticut and Massachusetts. By 1914, with rumors of war in Europe, Nelson quit exhibition flying.

A Calm Retirement

Nelson worked for Curtiss and other defense plants during WWI, then opened an automobile garage in New Britain. He owned a series of aircraft in which, as his biographers explain it, “he would hop passengers on weekends or fly just for the sheer joy of flying.”

Eventually Nelson retired, quit flying altogether and moved to New York where he died in 1964. By then, Beatlemania dominated international headlines and the then-secret SR71 Blackbird flew Mach 3. He had outlived most of his peers of the exhibition era, but most of Nelson’s later acquaintances would be hard pressed to imagine his name in headlines surviving death-defying crashes and splashes.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal. She has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.