BENDIX-MADE

“While our company designs and builds missiles and space systems, sophisticated aviation instruments and literally thousands of highly-engineered products, many people who recognize the Bendix name connect it with an automatic washer we never marketed.”

– Bendix Energy Controls Division “Log,” September 1973

I recently received a collection of photographs that had not seen the light of day for decades while in the file cabinets of Miriam Seymour. Seymour has a long career in aviation as an airport administrator, pilot and magazine author, which accounts for the diverse subject matter in her old files. Before computer scanning and digital cameras, the only way to reproduce a photograph of a Douglas DC-3 or Curtiss Condor for a newspaper or magazine article was to get permission to take the photo or request it from a public relations office. Glossy eight-by-ten-inch black-and-white images taken of carefully staged aircraft, special equipment, factory assembly lines and smiling pilots were freely offered by corporate marketing departments. “Stock photos” appearing in any publication meant free advertising.

In capital letters across one of Seymour’s aging manila envelopes was the word “Bendix Washing Machine.” What was this doing among pictures of 1940s aircraft? In the same envelope were engineering drawings for small aircraft, a Bendix newsletter from 1973 and photographs of the famous Bendix Aviation trophy. I didn’t have to read the inscription on the reverse to recognize Jimmy Doolittle and Mary Pickford at the finish line with trophy winner Doug Davis shaking hands with Mr. Bendix.

There is no better way to tell the rest of the Bendix story than with these enlarged photographs.

Automobile Starters, Brakes and the “Personal Airplane”

Vincent Hugo Bendix [1881-1945], an inventor from Illinois, formed the Bendix Aviation Corporation in 1927 in South Bend, IN. Bendix had already gained recognition for his successful invention of an electric starter for automobiles and advanced vehicle braking systems. Bendix also took over companies making aviation magnetos and carburetors. In order to increase interest in aviation and boost sales, Bendix created a trophy in 1931. This would be given to the pilot who established the fastest transcontinental speed record, initially flown from Burbank, CA, to Cleveland. Beginning in 1946, the Bendix trophy race departed and finished at various cities and was held each year until 1949, with a break during WWII. The original trophy was duplicated and given to the winners, among which were some of America’s most endearing and legendary aviators:

1931 Maj. James “Jimmy” H. Doolittle

1933 Roscoe Turner

1936 Louise Thaden and Blanche Noyes (first year women were allowed to compete against men)

1938 Jacqueline Cochran

Hollywood stunt pilot Paul Mantz won the Bendix trophy three years in a row (1946–1948).

Pioneer aviator Davis won the Bendix trophy in 1934. That same year, he was killed while participating in the Thompson air race in Cleveland.

Between 1946 and 1962, the race was renamed for the “Jet Class” and between 1998 and 2011, it was transformed into the Aviation Safety Award sponsored by Honeywell/Bendix.

The Boom that Never Came

Attempting to minimize the postwar WWII recession, the U.S. government theorized that once back home, aviators would want to continue to fly. “The idea of an airplane produced and sold the same way as an automobile took hold,” wrote George Larson in 1964. “North American launched the Navion. Republic launched the Seabee — both failing to capture the huge market forecast for them, but at least we remember them. Things worked out differently for the three airplanes launched by Bendix Aviation Corporation. All of them managed only a very brief moment on the world’s stage and then . . . oblivion.”

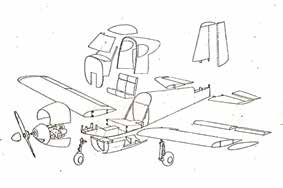

For their ambitious “Personal Airplane Project,” beginning in the summer of 1945, Bendix designed two versions of a small two-seat aircraft it named the Model 55. Both versions were an all metal, low-wing aircraft with side-by-side seating and tricycle retractable landing gear. The Model 55 was powered by a 100hp Franklin using an Annesley two-position controllable pitch propeller, producing a top speed of 148 mph. At the same time, Bendix designed a four-seat plane named the Model 51 which was also an all-metal construction with retractable tricycle gear. The Model 51 was designed to be either a land plane or adapted as an amphibian (with revisions to the hull and added tip floats on the wings). The manufacturing procedures at the Bendix factory were set up like the production of automobiles. By all accounts, each of the Bendix designs was innovative and met the requirements for approved type certificates.

About a dozen aircraft were built, with a larger production to be manufactured in Michigan and Texas. Just as Bendix employees were expecting a brilliant future in general aviation, the board membership changed and support ceased abruptly. In May 1946, the Bendix Personal Airplane Project was dropped entirely. “Hundreds of engines were sold off,” writes Larson, “and the finished planes were donated to local universities and high schools.”

About a dozen aircraft were built, with a larger production to be manufactured in Michigan and Texas. Just as Bendix employees were expecting a brilliant future in general aviation, the board membership changed and support ceased abruptly. In May 1946, the Bendix Personal Airplane Project was dropped entirely. “Hundreds of engines were sold off,” writes Larson, “and the finished planes were donated to local universities and high schools.”

By 1960, Bendix had perfected newly designed automobile brakes and electric fuel injections systems as well as a small line of bicycles. In 1971, they introduced the first anti-locking brake systems. Between 1982 and 2002 the Bendix name merged, combined and was eventually enveloped by Honeywell and then Knorr-Bremse in the U.S. and international affiliates.

. . . about that Washing Machine

During the mid-1930s, Bendix was also manufacturing hydraulic brakes when he leased part of his factory to two inventors of an automatic washing machine. In exchange for 25 percent of their stock, Bendix allowed his name to be used on the machine. “Bendix was assigned the task of producing certain components for the machines but that is as close as we came to the washer,” explains the editor of the Bendix “Log.” The washing machine was an immediate success, but in 1940, Bendix sold its stock. That should have been the end of that.

But, ask the seniors among your family and friends what first comes to mind with the name “Bendix.” It won’t be automobile brakes or starters. It won’t be missiles. It won’t be radar or “personal aircraft.” It won’t be Jimmy Doolittle.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author who has received the DAR History Medal and Honorable Mention from the New York Book Festival. She has appeared on the History Channel and in PBS documentaries.

For more information, visit www.GiaBKoontz.com.