OFF THE BEATEN TRACK Finding your Aviation Ancestry

One of my favorite web sites is Paul Freeman’s, “Abandoned and Little- Known Airfields,” which is divided by state and lavishly illustrated with rare maps, photographs, documents and updated information on field closures in obscure places. I was scrolling through the web pages for the area eastern region of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and found a plaque commemorating the Kurtztown Airport. In 1995 the airport celebrated its 50th anniversary with a ceremony and hopes for the future. Sadly, this charming general aviation field has recently been closed, and despite objections by many area residents, is destined to be the location of a shopping center. Pennsylvania has seven major airports. It also has over 130 public use airfields, but the plaque at Kurtztown reminds us that we are losing many of our once thriving small municipal and regional airports across America.

While exploring the western region of Pennsylvania in search of our aviation history, I discovered the origins of the famous OX5 engine club, a remarkable tribute to the Tuskegee Airmen, and a town determined to rename their airport for a local Early Bird. These stories symbolize the theme of my column this year in which I am encouraging you to be on the alert for your aviation ancestry.

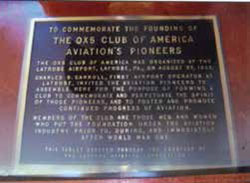

In 1955, a plaque was placed at Latrobe Airport located near Pittsburgh, to commemorate the founding of the OX5 Club of Pennsylvania. Latrobe is now Arnold Palmer Regional Airport (LBE) and the OX5 Club became the national organization known as the OX5 Aviation Pioneers. This unlikely name for a group of pilots is derived from the Glenn Curtiss engine first built in 1910. Following a series of prototypes and collaborating with power plant designer, Charles Manley, Curtiss manufactured thousands of OX5s. During the 1920s, when surplus engines were inexpensive, the OX5 was used on general aviation aircraft such as the Laird Swallow, Pitcairn PA-4 Fleetwing II, Travel Air 2000, Waco 9 and 10, the American Eagle, the Buhl-Verville CW-3 Airster, and some models of the Jenny.

“Poor is the nation having no heroes. Shameful is the one having them that forgets.” – Unknown Author

Latrobe is about seventy miles from the town of Washington which proudly claims David Lloyd “DeLloyd” Thompson [1888-1949] as one of their own. Thompson shortened his name by combining his first initial with his middle name. His flying friends called him “Dutch.” By 1910, Thompson had made a name for himself racing automobiles when he became air-minded.

At St. Louis, Missouri, Thompson studied under the expert supervision of the Wright brothers’ first instructor, Walter Brookins [1889-1953]. Wright biplanes had dual controls, allowing students to sit beside their instructor gaining valuable experience before a solo. Thompson was a quick study with remarkable instincts for operating the tricky controls of his Wright Model B machine. He was soon hired as a flight instructor for the famous Maximillian Theodore Liljestrand, otherwise known as Max Lillie, at Cicero Field in Chicago. He received his aviator’s license from the Aero Club of America in 1912, just prior to his five year career in exhibition flying. When he was not staging automobile vs. aircraft races with Barney Oldfield, he made aviation history with new stunts and briefly held altitude and cross-country records. In July, 1913, Thompson was one of a dozen entrants for America’s first hydro-aeroplane race which followed the shore of Lake Michigan from Chicago to Detroit. Thompson was ready to fly his Walco flying boat biplane, equipped with a 50hp Gnome engine, but according to historian Henry Villard, “on the day of the race it was one of the stormiest in years on Lake Michigan.” Thompson dropped out. On September 2, at Mahanoy Park, northwest of Allentown, PA, he experienced his first accident flying his Wright biplane. The damage to man and machine was minimal, enabling Thompson to fly almost every day for the next two months, touring Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Wisconsin and Kentucky.

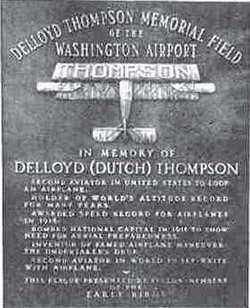

At the peak of his exhibition years, Thompson was compared to the fearless aviator, Lincoln Beachey. Considering the level of danger for which Thompson was famous, and how often he was in the air, his safety record is remarkable. During 1917, Thompson retired from exhibition flying and rarely flew until twenty years later while testing a monoplane of his own design. In 1949, Thompson died in his sleep at age 61. The residents of Washington named their airport “DeLloyd Thompson Memorial Field,” marking its entrance with two handsome bronze plaques.

Over the next twenty years Washington Airport (WSG) expanded beyond the original gates and the plaques were relocated in 1969 to the airport administration building. What followed next could have led to another sad chapter of “Little Known and Forgotten Airfields.”

During remodeling of the administration building the heavy plaques were destined for the scrap heap. A quick-thinking city employee diverted them to the local historical society where they were placed on display. Thompson’s name faded from memory until 2013 when the residents of Washington again urged their county officials to re-dedicate their taxiways and runways as “DeLloyd Thompson Memorial Field.” If they are successful, the bronze plaques will return to the airport. Hooray for Washington, Pennsylvania.

Inspire, Enlighten and Challenge

“It is amazing what you can find when you go off the beaten track!” writes Michael Lynaugh on his web site of professional photographs and comments. “In 2010 I was driving to Virginia from Florida on I-95 and saw a sign in South Carolina that said, Tuskegee Airmen Memorial. . .so I decided to pull off and see what I could find.” Lynaugh soon found a monument replete with a bold sculptured bust of a pilot and descriptive bronze plaques. His reaction was not uncommon. “I was very surprised to find that this tiny airport was the training field for the Tuskegee Airmen, as well as a POW camp for foreign prisoners of WWII.”

The Low country Regional Airport (KRBW) in Walterboro, SC, also known as the Walterboro Army Air Field, is not exactly “tiny.” It is the largest general aviation airport in that state. I confess it is not the first place that I would have looked for a tribute to the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group of the United States Army Air Forces, nicknamed the Red Tails for the color painted on their P51 Mustang. I checked at Moton Field in Tuskegee, Alabama (for which the airmen were named) and discovered the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site at which is located the Hangar One Museum (but no monument).

No pilots were trained at or near Sewickley, Pennsylvania, a town with a population less than 3,000 during WWII. Nevertheless local historians spent six years gathering documentation which would ultimately list 100 men and one woman from Western Pennsylvania as members of the famous all-black squadron of WWII. Eight of these men were residents of Sewickley, including a father and son. All of their names now appear on tall monuments in a new plaza entrance to the Sewickley Cemetery. Among those listed is Frank Hailstock who was born and raised in Sewickley. Hailstock served as a radioman on a B25 bomber. His son, Terry, attended the ceremonies commenting that his father would have been pleased with the recognition. The editor of the local paper in Sewickley, Pennsylvania, once wrote that monuments are meant “to inspire, to enlighten, and to challenge us. Memorials give us a sense of belonging, and connect us to your past.”

Hailstock’s grave lies near what is thought to be the largest outdoor tribute to the Tuskegee Airmen in the U.S. But, you have to wander a little off the beaten track along the Ohio River to find it.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author who has received the DAR History Medal and Honorable Mention from the New York Book Festival. She has appeared on the History Channel and in PBS documentaries. For more information, visit www.GiaBKoontz.com.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author who has received the DAR History Medal and Honorable Mention from the New York Book Festival. She has appeared on the History Channel and in PBS documentaries. For more information, visit www.GiaBKoontz.com.

Here are the URLs for some of the sites which I have mentioned. Spoiler alert: If you log onto Freeman’s Abandoned and Little- Known Airfields, and Ralph Cooper’s Early Aviators, you may lose track of time. All photographs in this article are from these web sites and others not listed, unless otherwise noted.

Abandoned and Little-Known Airfields www.airfields-freeman.com

Early Aviators www.earlyaviators.com

The OX5 Aviation Pioneers ox5.org

The Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site - Museum Hangar One www.nps.gov/tuai/index.htm