Of Balloons and Parachutes - The Remarkable A. Leo Stevens (1877?-1944)

By Giacinta Bradley Koontz

A female mannequin with perfect alabaster skin and long eyelashes greets visitors in the entrance to the Hill Aero Space Museum at Salt Lake City, Utah. Frozen in a graceful pose within her Plexiglas case, she wears a gauzy and diaphanous white gown. At first glance, she seems out of place amid the camouflage and anti-aircraft guns, but she won her special place in an aviation museum as a parachute seamstress during WWII. When considering that everything from tires to candy wrappers was recycled toward the war effort, it makes sense that this bride’s gown is made from parachute silk. Brides are now more likely to wear a parachute on their back while taking their vows during a free-fall jump than to wear it as a dress.

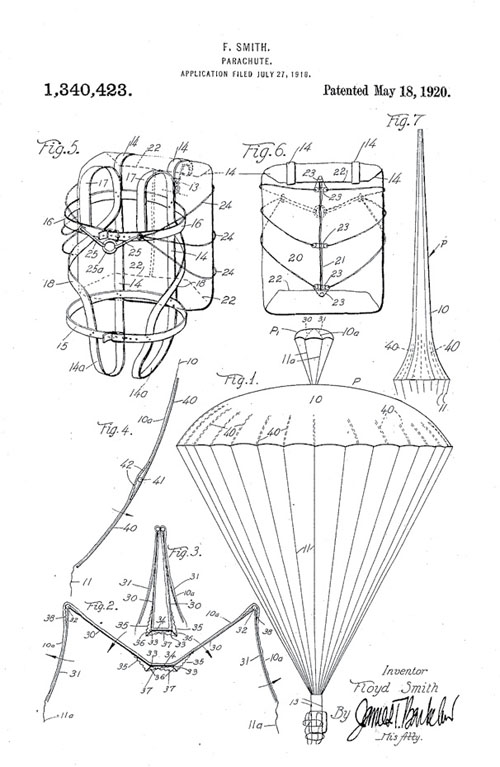

Today’s parachutes are not radically different than the first ones invented before WWI by several safety-conscious aviation pioneers including Charles Broadwick, Ralph Carhart, Floyd Smith, Leslie Irvin and A. Leo Stevens. Although daredevils had used parachutes for stunts from balloons, bridges and even the Statue of Liberty, the static-line drop from an aircraft proved dangerous as the rigging snagged on the tail or in the landing gear. Smith, an aviator associated with Glenn Martin, is credited with inventing the manually-operated parachute while he, Stevens and Irvin conducted experiments at the U.S. Army’s McCook Field in Ohio during 1918.

“Smith and Irvin had each independently arrived at similar configurations for a back-style freefall parachute assembly,” writes researcher Jim Bates, “though history is not clear as to who actually was first.”

The most colorful character among the inventors who first valued human life above the advancement of an aircraft design or entertainment at air shows, was Stevens, otherwise known as “Aeronaut No. 1.” As early as 1908, Stevens conceived the design of a free-fall parachute but failed to perfect the rigging apparatus.

“The U.S. Government issued many patents to designers of innovative parachute concepts before WWI,” says Bates. “However, patents were for concepts only, and there doesn’t seem to be any record of most ideas even reaching a prototype stage.”

The Young Aeronaut and Human Bomb

Stevens, who was born in Ohio, was fascinated with balloons as a child. He became a showman early on and always loved the spotlight. The facts of Stevens’ remarkable life are difficult to separate from fictional accounts. Interviewed often, Stevens retold the tale of his first ascension at age 11 when he volunteered to help a balloonist offering tethered rides at a local park near Canton. “I shoveled the iron, carried the acid, helped to haul the water, and chopped the ice — ruining my knickerbockers with the acid,” he said.

Stevens, who was born in Ohio, was fascinated with balloons as a child. He became a showman early on and always loved the spotlight. The facts of Stevens’ remarkable life are difficult to separate from fictional accounts. Interviewed often, Stevens retold the tale of his first ascension at age 11 when he volunteered to help a balloonist offering tethered rides at a local park near Canton. “I shoveled the iron, carried the acid, helped to haul the water, and chopped the ice — ruining my knickerbockers with the acid,” he said.

After being denied a ride, Stevens climbed inside the unattended balloon, fully inflated with hydrogen gas. Stevens cut away the ropes and shot into the air. Crash-landing into a tree miles from home, Stevens was unhurt but his parents were required to pay for the damaged balloon. He left home the following year to perform high wire acts and parachute jumps from balloons in traveling shows. His only brother, Frank, was with him. Frank and Leo were billed as “The Boy Wonders of the Air” during the 1890s, with Frank making the first jump over Manhattan, NY. Frank quit and established an awning manufacturing company and Leo became an avid balloonist. At one point, Leo changed his name to “Aeronaut No. 1 Stevens.”

Stevens began manufacturing balloons in New York around 1893. He was open to any business opportunity, even the bizarre. One failed scheme involved a balloon service flying gold miners to the Klondike in 1897.

In September 1901, the New York Buffalo Commercial newspaper reported, “Leo Stevens, in the human bomb act, gave the people at the Pan American Exposition the worth of their money. A balloon was sent up from the stadium at one o’clock. Trailing behind it was a big round ball. This was the bomb, and inside was Stevens.”

Once the balloon had reached its highest altitude, the “bomb exploded” and out burst Stevens, “falling rapidly earthward, a closed parachute behind.” As spectators watched, Stevens dropped 100 feet before opening his parachute and gliding gracefully and safely to earth. Soon thereafter he bought a dirigible, mastered the controls, and improved its design. In his Manhattan Beach, NY, workshop he built the Pegasus, a non-rigid dirigible with an 85-foot envelope almost 20 feet in diameter, and powered by a 7.5 hp engine. Stevens piloted the Pegasus in 1902. It made its debut flight over Brooklyn, NY, on the same day as another dirigible owned and piloted by Edward Boyce. Before both Stevens and Boyce made safe landings, their controlled flights caused a sensation.

Ladies in the Air

Mary Miller became the first American female dirigible passenger (with Stevens at the controls) in Pennsylvania in 1906. Stevens encouraged women to go aloft, and both his first and second wives were avid balloonists. His most famous female passenger was actress Pearl White. With Stevens as the stunt pilot, she feigned rescue by balloon for the 1914 silent film series, “Perils of Pauline.”

Mary Miller became the first American female dirigible passenger (with Stevens at the controls) in Pennsylvania in 1906. Stevens encouraged women to go aloft, and both his first and second wives were avid balloonists. His most famous female passenger was actress Pearl White. With Stevens as the stunt pilot, she feigned rescue by balloon for the 1914 silent film series, “Perils of Pauline.”

Stevens was appointed instructor to the Signal Corp in the “handling of aerostats” (tethered observation balloons) for the United States Balloon Corp. in 1907. Later training at Nebraska and Virginia included experiments with radio transmission, aerial photography and instruction on balloon manufacture.

Stevens brought his giant balloons to the first U.S. International Air Meet held at Dominguez Hills, Los Angeles, CA, in 1910. Aircraftmagazine recognized him as one of the “Big Men of the Movement,” along with such notables as Count Von Zeppelin, the dirigible builder from Germany. On Long Island during 1911, Stevens attempted lessons in a Burgess biplane which crashed and ended his apparent interest to fly a fixed-wing aircraft.

The following year, he managed the career of exhibition pilot Harriet Quimby. Stevens negotiated a lucrative salary for Quimby to appear in the Harvard-Boston Air Meet of 1912. At that time, open cockpit aeroplanes rarely had shoulder or lap harnesses to hold them securely in place. Both Quimby and her passenger were thrown out of her two-seat Bleriot as she returned from a flight over Dorchester Bay near Quincy, MA. Quimby and her passenger fell to their deaths as Stevens and thousands of spectators watched. Stevens was thereafter determined to perfect a parachute which could be used in various types of aircraft.

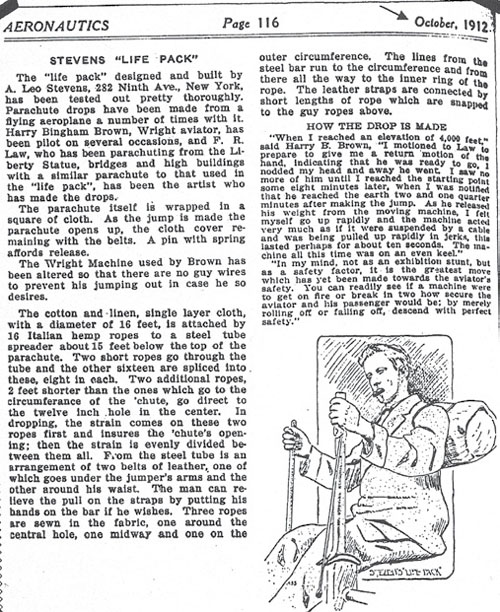

He tested and continued to perfect his first parachute series which he named “Stevens Safety Chute.” He eventually refined the materials and the release mechanisms used. It is generally accepted that Stevens contributed to the invention of the rip chord, even if he is not credited with its later patents.

He tested and continued to perfect his first parachute series which he named “Stevens Safety Chute.” He eventually refined the materials and the release mechanisms used. It is generally accepted that Stevens contributed to the invention of the rip chord, even if he is not credited with its later patents.

Stevens organized many of the first American Aero Clubs, encouraged model airplane enthusiasts, and never abandoned his love of ballooning. In 1920, he agreed to take a scientist into the atmosphere to determine if life existed on Mars. This and other unfulfilled ventures were but footnotes to Stevens’ resolve to design a parachute and other safety features for pilots. A medallion was awarded annually in his name during the 1940s and 1950s.

At his last home in Cooperstown, NY, neighbors recall Stevens making parachutes in his shop over his garage and giving children lessons about ballooning. While en route to Washington, D.C., in 1944 to file another patent for a parachute, Stevens stopped to spend the night at his brother’s home and died in his sleep. Stevens is buried at Fly Creek, NY. His gravestone is inscribed “Aeronaut No. 1.”

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.