Lack of Assertiveness

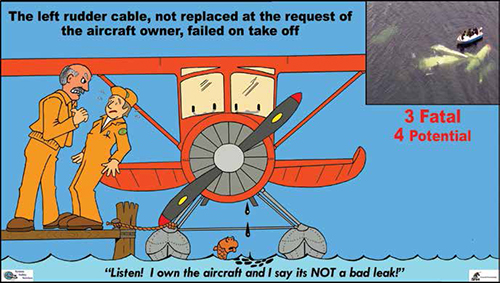

Lack of assertiveness has been a contributing factor in way too many accidents. Looking at the cartoon takes us back to a fatal float plane accident up north many years ago. A conscious aircraft maintenance engineer (AME) found a corroded rudder cable just inside the empennage on a routine annual inspection. He brought it to the attention of the owner of the aircraft, who said that he would order a cable for the next inspection as the cable didn’t look that bad. Not long after, the cable failed on a cross wind take-off, allowing a wing to dip and the aircraft to cartwheel violently and sink in the water. Four passengers were able to escape the sunk aircraft that hung under one float, but the owner, who was flying and not wearing the available shoulder harness, was not one of the fortunate four. By not wearing the shoulder harness, he had received a blow to his head that likely rendered him dazed long enough for him to drown.

The AME was in the first boat to arrive on the scene. Looking down through the water, he saw one end of the broken cable attached to the rudder. One can only imagine the horror he must have felt when he realized that he had contributed to this error. His lack of assertiveness in doing what he knew should have been done had cost three lives. The license suspension by the regulatory body meant nothing to him. He never touched an aircraft again and left the aviation industry.

Lack of assertiveness is failing to act in a bold and confident manner on safety concerns. It also is failing to listen to views of others before making a decision. Failing to listen puts you in the aggressive category. Listening means that you are assertive and willing to hear what others have to say, but you still make the safety decision after taking their views into account. The image below illustrates that important balance.

We (maintenance personnel) are often not good communicators and don’t always speak up when we should. The following speech by Giselle Richardson, a dear and departed friend of mine, says it better than I ever could. I first heard that presentation and met her at a banquet for an industry guidance committee to Transport Canada, of which I was a member, way back in 1992. I asked and she gave me a copy to do with as I wished. She had the ability to shake your hand and know more about you than you knew about yourself, just from that brief encounter. See if what she said about us back then is just as true today.

“Cinderella In the Flight Department”

Some years ago, flight operations began to discover the value — indeed, the need for — training in the human element for their managers and staff. This activity has evolved from being a rarity to a regular feature in most flight departments and focuses mainly on flight crews and management. Although the seminars we offer are advertised as being useful for flight and ground crews alike, invariably, in our sessions, pilots out number mechanics by about five to one. How come? Why is this type of training not made available to nearly the same degree in the maintenance departments? Aren’t mechanics people, too? Don’t maintenance directors, crew chiefs, and supervisors need skills to communicate and to manage and to motivate? Don’t mechanics need to learn to deal with stress, too? Why aren’t they getting the same attention the flight groups get?

The answers to these questions, I am afraid, come to roost squarely on the shoulders of those responsible for the maintenance departments.

You might know that different professions are characterized by different predominant personality profiles. If you doubt it, the next time you go to the NBAA annual show, pause in the aisles and look around you. Use your intuition and you will quickly be able to pick out the pilots from the salesmen (well, not always!), the salesmen from the design engineers, and the mechanics from all the others.

Why? These traits are found to predominate in the maintenance area: commitment to excellence, willingness to put in effort and hours, integrity, distrust of words, dependability, tendency to be a loner, modesty (no desire to be in the spotlight), not liking to ask for help, tending to be self-sufficient, thinking things through on our own and not sharing our thoughts too frequently or thoroughly. (We have not met many mechanics whose spouses say, “I wish my spouse would shut up and let me get a word in edgewise.”)

Most of these qualities are assets, provided that they are not carried too far. Let’s look at self-sufficiency, plus the habit of doing your thinking without checking it out with others. It’s my contention that both contribute to the one-down role that maintenance too often holds in the flight department. In other words, one of the reasons the maintenance group so frequently finds itself in the position of the second-class citizen in the flight department is because, in a way, it is asking for it.

Speaking to an aviation group some time ago, I said, “When things go wrong, pilots bitch and mechanics sulk.” You have all heard about the squeaky wheel. Those who suffer in silence are less likely to get attention.

The business of not asking has become a habit for some of you. Let me give you an example. Not long ago, we were conducting team effectiveness programs in a large corporate flight department. The company is one that does not cut corners and generally responds to reasonable requests from its manager. To our amazement, we found out that whenever pilots and mechanics went to ground school (even when they were there together), mechanics received a lower allowance for meals, etc., than the pilots did. We made loud and indignant noises about this to the aviation manager, only to learn that it was the chief of maintenance who established the cost-of-living allowances for his people when they were traveling. The aviation manager had no objection to increasing the allowances to match those of pilots; he was simply going along with the chief of maintenance’s preference.

With that kind of behavior, is it any wonder that Cinderella pushes out cinders and garbage in the maintenance area while her pilot sisters go to the ball in their brocade gowns? This attitude invites others to see mechanics as less important than other members of the department. If you invite people to kick you, there is bound to be someone who will accommodate you.

This article is an invitation to mechanics, and especially to the managers in the maintenance area, to rethink how they perceive their roles in the department, the contribution their people make to the company, and the ways they have at their disposal to make sure that they are duly recognized.

Space available prevents our detailing the myriad instances where some clarity and assertiveness would serve the maintenance group well: salaries, working hours, technical training, and (given our bias) the fact that mechanics — like other human beings — can benefit from assistance as they find their way in life, just like the rest of us, whether or not they are currently in a period of professional or personal or family crisis. That is to say that employees in the maintenance area require systematic psychological maintenance like the rest of us, and will benefit from any kind of training that enables them to understand human behaviour better, to see how they unwittingly contribute to some of their problems, and — most importantly — to ensure that they find some ways to become comfortable with more appropriate behavior.

The first step, of course, is for the management group of the maintenance area to upgrade their own people skills, to get to understand how they limit their ability to use their talents, their experience, their wisdom and their compassion for the benefit of their people. They need to recognize that they have two roles to play in the organization: to contribute to the success of the flight department, and to stand up for, defend, represent and develop their own staff. The two are sometimes in apparent conflict. More importantly, the second role too often conflicts with the manager’s personal style as described above. Too often, he or she opts for the first at the expense of the second.

The mechanic has his or her 50 percent of the deal, too. Does he or she swallow frustrations and give up too easily? (“I mentioned it to him once five years ago, but he didn’t do anything, so what’s the use of bringing it up again?”) Does the mechanic assume — like the wife who enjoys being a victim — that “if he really loved me, he’d know what I want,” or does the mechanic state his or her point of view clearly, making frustrations, satisfactions and preferences known? Does the mechanic give his or her boss the kind of feedback needed to do his or her job properly and easily?

Bear in mind that what I am recommending is not revolution but equity and responsibility. I’m pushing for a psychological coming-of-age of the maintenance people in the aviation industry. It’s time to have a bonfire and get rid of what a friend of mine calls “the humbleshit” and give to this excellent group of professionals the position they deserve in the industry. It’s largely up to you!

Summary

With that, Giselle has told us what we have to do. It might be a lot easier said than done.

Our next topic will be lack of communication, which ties into our “humbleshit” problem.

Gordon Dupont worked as a special programs coordinator for Transport Canada from March 1993 to August 1999. He was responsible for coordinating with the aviation industry in the development of programs that would serve to reduce maintenance error. He assisted in the development of Human Performance in Maintenance (HPIM) Parts 1 and 2. The “Dirty Dozen” maintenance safety posters were an outcome of HPIM Part 1.

Gordon Dupont worked as a special programs coordinator for Transport Canada from March 1993 to August 1999. He was responsible for coordinating with the aviation industry in the development of programs that would serve to reduce maintenance error. He assisted in the development of Human Performance in Maintenance (HPIM) Parts 1 and 2. The “Dirty Dozen” maintenance safety posters were an outcome of HPIM Part 1.

Prior to working for Transport, Dupont worked for seven years as a technical investigator for the Canadian Aviation Safety Board (later to become the Canadian Transportation Safety Board). He saw firsthand the tragic results of maintenance and human error.

Dupont has been an aircraft maintenance engineer and commercial pilot in Canada, the United States and Australia. He is the past president and founding member of the Pacific Aircraft Maintenance Engineers Association. He is a founding member and a board member of the Maintenance And Ramp Safety Society (MARSS).

Dupont, who is often called “The Father of the Dirty Dozen,” has provided human factors training around the world. He retired from Transport Canada in 1999 and is now a private consultant. He is interested in any work that will serve to make our industry safer. Visit www.system-safety.comfor more information.